Archibald Robertson, The Origins of Christianity, International Publishers, 1954, rev. ed. 1962.

HOW MAN MADE GOD

To many who are under the influence of traditional education it may seem that man is naturally religious. The Bible, the teaching of which is obligatory in most of our schools, depicts mankind as worshipping God from the earliest times. It is one of the commonplaces of religious teaching that the world about us proves the existence of an almighty and loving Creator, and that only perversity refuses to acknowledge and glorify him.

On reflection it is evident that we are not naturally religious. Those of us who believe in a religion do so only because we were taught it. The Churches themselves recognize this fact by using their political power to enforce religious teaching in our schools. Not only so, but the religion taught would be unintelligible to people who had not attained a certain level of culture. To take an obvious example, the first article of the Apostles' Creed affirms belief in "God the Father Almighty". The word "father" is at once intelligible to us, but would be unintelligible to primitive savages. There was a time when man was unacquainted with the fact of paternity; in fact some tribes are unacquainted with it today.

Man was always a social animal. Unless he had been, he would not have survived in the struggle for existence against beasts of prey and the rigours of climate. The basic difference between primitive, barbaric and civilized society is in productive equipment and the social relations to which this gives rise. Take away from man the steam and electric power of modern industrialism; take away the printing press, mariner's compass and fire-arms of early capitalism; take away the art of writing evolved in ancient civilization; take away even the pastoral, agricultural and metallurgical arts achieved by prehistoric barbarism -- and man is back on the primitive level.

With primitive productive equipment goes a primitive economic structure; and with this goes a primitive ideology. This does not mean that the primitive is a fool. The Australian aborigines, though ignorant of pottery and agriculture, are clever enough to make the boomerang. The somewhat less primitive Melanesians, though ignorant of metal-work, are skilled in pottery, boat-building, fishing and gardening. These people are rational enough about what they know how to do. But where an element of luck enters in, the distinctive ideology of primitive society begins. This takes the form of magic, that is, of action designed to control events which the primitive has no real means of controlling -- the weather, the multiplication of plants and animals, and so forth. The commonest form of magic is "sympathetic" magic, in which you try to produce an effect by doing something like it. To multiply a species you mimic it in dance or song. To make it rain and thunder you whirl a noisy instrument called a "bull-roarer", drum on a kettle, or scatter water on the ground. Other magic is used to prevent death in child-birth, and to initiate youths into full membership of a tribe. The most primitive societies have magic, but no religion. Among "the aborigines of Australia", says Frazer, "magic is universally practised, whereas religion in the sense of a propitiation or conciliation of the higher powers seems to be nearly unknown."1 Tribal magic is handed down by tradition along with such genuine knowledge as the tribe possesses. Youths at puberty are initiated into both. To explain rites of which no rational account can be given, myths are told. Thus in Australia uninitiated boys are not allowed to see a bull-roarer, but are told that its noise is the voice of a mythical monster or ancestral spirit. On initiation they learn to use it, that is to practise thunder-making magic, causing "the rain to fall and everything to grow up new".

Bull-Roarer |  Twirling a Bull-Roarer |

Many barbaric tribes have a word denoting power of any kind, whether in men, animals, plants or inanimate objects -- orenda, among the Iroquois, wakanda among the Sioux, manitou among the Algonquins, mana among the Melanesians, and so forth. Such terms may be rendered "spirit", provided we remember that they do not necessarily imply personality. Such power resides in a man, but also in a beast, bird, tree, stone or thunder-storm. "No man has ever seen wakanda" said an Omaha elder to an anthropologist.2 Under primitive communism this is as near as man gets to an idea of God.

There is evidence in civilized societies that religion arose from tribal magic such as is still practised by primitives. But it is a considerable step from the primitive magic of the Australian aborigines o the developed religions of ancient civilization. In the one case there is ritual, but not worship; in the other the ritual is part of the worship of supposed external beings -- gods. This is the difference between magic and religion properly so called. It is impossible to deal with so vast a development within the compass of this chapter except in a summary fashion from which much is necessarily omitted.

The passage from magic to religion is connected with the emergence from primitive communism of the beginnings of class society. In the most primitive societies there is no special class of rulers. Affairs are managed by the elders; and anyone may become an elder by living long enough. But in societies with a somewhat better productive equipment, as in Melanesia, the tribal surplus of food is enough to keep an unproductive class of magicians, and magicians with a run of luck to their credit live on offerings. Like other successful men, they have an extra share of mana. As Frazer puts it, "magicians or medicine-men appear to constitute the oldest artificial or professional class in the evolution of society".3 "Round every big magician", says Malinowski, "there arises a halo made up of stories about his wonderful cures or kills, his catches, his victories, his conquests in love."4 The tribe credit him with power over the forces of nature; or rather to them he is a force of nature -- while his luck holds.

The illusion is sustained by the customs associated with totemism. The primitive tribe is made up of different clans or kinship-groups. Each clan then uses its traditional magic to multiply a particular species -- its totem. But it does not eat its totem; it leaves it for the other clans of the tribe. The clan is said to be descended from its totem, and dire consequences are alleged to follow the infraction of the taboo. Totem, we may note, is simply an American-Indian word for "clan". The custom by which the magician, representing the clansmen, dresses up and impersonates the totem-animal during the multiplication ceremonies helps to confirm the illusion that he is in a special sense the totem-animal -- the clan incarnate.

There is good evidence that the magician or medicine-man himself was the first god. In ancient society priesthood, kingship and godhead are only gradually separated. Early man, says Frazer, does not "draw any very sharp distinction between a god and a powerful sorcerer". Indeed in our sense of the word " the savage has no god at all ".5 On ultimate analysis priest, king and god all go back to the early magician wielding his supposed mana for the good of the tribe.

In this embryonic phase of class society ruling is a dangerous trade. The luck of a magician does not last for ever. He is bound to have failures. Some failures may be cancelled by successes; others may be explained away by accusing enemy magicians or witches. But sooner or later the magician's claims cease to be credible. Then it is a bad day for the magician. He will be insulted, beaten, killed or driven into exile, as happens to this day in various African tribes. A rival may challenge him to fight, kill him and reign in his stead, as in the famous case of the "king of the wood" in ancient Latium ("the priest who slew the slayer, and shall himself be slain"), or as formerly in Bengal, where whoever killed the king was immediately acknowledged as king.

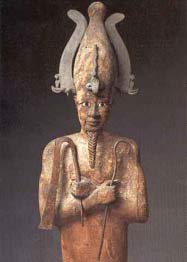

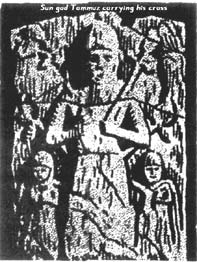

This is the more likely to happen when primitive technique gives place to agriculture. The rise of agriculture adds to the responsibilities of the magician, and therefore both to his prestige if successful and to his discredit if unsuccessful. The nature of paternity is now known; for developed agriculture (over and above mere gardening) depends on the domestication of animals, and ignorance of the nature of paternity can hardly survive the possession of livestock. On the principles of sympathetic magic, therefore, the virility of the magician-chief, now become a "corn king", is believed to promote the fertility of the soil. But if so, a corn king with failing powers is of no use. It is better to kill him, as was done by the ancient Ethiopians, and even until modern times by some tribes of the upper Nile and Congo. Or, to make sure, he had better die after a fixed term of office that his power may go into the earth unabated. The custom of killing the corn king after a fixed term was formerly the rule even in modern times in some parts of southern India and Africa. Popular tradition in countries widely separate in space and time speaks of a god who dies and lives again for his people -- Osiris in Egypt, Tammuz among the ancient Semites, Attis in Asia Minor, Dionysus in Greece, even Odin among the peoples of the north.

Osiris |  Tammuz |  Attis |

Dionysos |  Odin |

But with the rise of class society such treatment of chiefs becomes an anomaly. The passage to a pastoral and later to an agricultural economy increases the surplus food at the disposal of the tribe, makes it possible to keep slaves ("human cattle", as Engels puts it)6 and makes easy the appropriation of wealth by the chief. The chief becomes rich and powerful, and yet he is expected after a term of years, or at the first sign of failing powers, to die that the tribe may live! Sooner or later, as we might expect, a chief whose time is up declines to die. In backward societies we have historical evidence of this. According to Diodorus, in the third century B.C. a king of Ethiopia, who had had a Greek education, was ordered by the priests to kill himself according to custom. He killed them instead. Potentates innocent of Greek have been just as ready to dodge their liabilities. A Portuguese historian cited by Frazer mentions a Kaffir king who refused to commit suicide according to precedent on losing a front tooth, and recommended his successors to follow his example. More usually the chief compounded for his immunity by sacrificing a substitute -- a son or, better still, a slave or someone else of no account.In the first civilizations, of course, it happened much earlier. After the urban revolution in the Middle East which ushers in civilization properly so called -- the concentration of populations before 3000 B.C. in cities such as those of Mesopotamia and Egypt -- and even more after the unification of cities in kingdoms under dynastic conquerors, the immolation of the ruler in person was unthinkable. To keep up the fiction that the divine king was killed, the substitute was treated as a divine king before being sacrificed. Thus in ancient Egypt, a victim impersonated Osiris, the corn-spirit, and was sacrificed in place of the Pharaoh, whose ancestors in prehistoric times had probably filled the role. This did not prevent the Pharaoh, when he came to die, from being venerated as Osiris just as if he had been the victim. At Babylon a condemned prisoner was annually dressed in royal robes, treated as king and allowed to enjoy himself with the king's concubines for five days before he was scourged and put to death. In Mexico before the Spanish conquest a prisoner was chosen a year beforehand, dressed as a god, worshipped as a god, feasted as a god, and children were brought to him to be blessed and sick folk to be cured, before he was killed and eaten at the spring festival. So with the growth of class society the king, by virtue of superior force, enjoyed the privileges of a magician-chief without his liabilities, while the victim picked for sacrifice shouldered his liabilities after a hollow show of privilege.

The custom of killing the magician-chief, or later a substitute, for the good of the tribe inevitably leads to a distinction between the god and his temporary representative. The successful magician who makes the rain fall and ensures your food supply is plainly stronger than you. But the unsuccessful magician who has fallen down on his job and has to be knocked on the head is plainly weaker than you. The magician, therefore, who succeeded yesterday and fails today is not the real author of your rainfall and food supply. The anomaly demands a myth to explain it. Once long ago in the heroic past there was a very great magician, the ancestor of the tribe, who showed how magic should be done. From him his successors derive their power. When they are successful, his spirit is in them. When they fail, his spirit passes to another. Here at last we have the idea of god apart from man, or at least from any known man -- an idealized magician-chief other than the real magician-chief who fails and dies. On the Egyptian monuments the Theban god Amun, for example, is depicted as a man with the head and horns of a ram. No doubt originally the magician-chief of Thebes dressed up in this way to perform the rites which multiplied the Theban flocks and herds. Inscriptions at Luxor show that the Theban Pharaohs of the eighteenth dynasty (about 1550-1350 B.C.) were held to be actually begotten by Amun, who in the form of the reigning Pharaoh impregnated the queen consort. Centuries later Alexander's claim to the throne of Egypt was confirmed by the oracle of Amun, which acknowledged him as the son of the god. In the same way in modern times the Shilluk tribes of the upper Nile held that their king, on whose health and strength their welfare depended, was a reincarnation of Nyakang, the divine founder of his line. In due course the Shilluk king was killed according to custom, and the son or other relative who succeeded him inherited his divinity. Among other Nilotic tribes, too, the ancestral spirit is believed to pass from each chief to his successor. The god, in short, from an individual magician-chief, the personification of a clan, has t become a projection of an ideal magician-chief, a personification of the ruling class in barbaric or early civilized society.

By the time, therefore, that civilization has emerged from barbarism, religion is already an amalgam of contradictory elements. Firstly it is a body of ritual traceable to primitive magic and carried out by priests or priest-kings, the civilized counterpart of tribal magicians, in order to ensure food-supply as well as subsidiary advantages to the community which they rule. Secondly it is a body of myths relating to the ritual.

The elaborate Egyptian theology which settled the mutual relations of different local deities does not necessarily represent the real belief of the priests. It merely means that, when Egypt was unified, they had to reconcile the claims of each local god with those of other local gods. When later under the eighteenth dynasty Thebes became the capital of Egypt, its god Amun was amalgamated with Re and Horus and became the supreme god. To the Egyptian peasant, who lived, laboured and died in his native place, the priest-made pedigree relating his god to other gods did not matter so long as traditional ritual made the sun shine, the Nile rise, the corn grow, the beasts breed and village life go on.

As in Egypt, so in Babylonia the unification of the country first under one city-state, then under another, led to priestly attempts to arrange the gods of different cities in an ordered pantheon. After Babylon had become the ruling city about 2000 B.C., its god Marduk annexed the ritual and myths of the other gods. He became Bel-Marduk, lord of light, who had conquered Tiamat, the dragon of the waters, made heaven and earth out of her dismembered body, and created plants, animals and men. This ancient creation-myth has come down to us in more than one version. In the older legends not the Babylonian Marduk, but Ea, the god of Eridu (in those days washed by the Persian Gulf) is the creator. Doubtless the myth was first suggested by the struggles of early settlers in Babylonia to reclaim land from the marshes of the lower Euphrates and Tigris. Another echo of early struggles with the hostile water-element is the flood-story, of which also we have more than one version. The flooding of the rivers on which they flourished must have been a standing threat to more than one early civilization, and particularly in the wide alluvial plain of Babylonia. The creation and flood stories in Genesis are Jewish adaptations of these Babylonian legends.

A notable feature of early religion is the progressive transference of its gods from earth to heaven and their transformation from magnified men into completely superhuman and celestial beings. The original god, as we saw, was a bigger and better magician-chief doing the things that a magician was expected to do -- making rain and multiplying the fruits of the earth, the beasts of the field and the fish of the sea; He was not too divine to die and be buried and for his tomb to be pointed out. The annual cycle of life and death in nature, on which man's life depended, was for long the only measure of the year. But even before civilization arose a more exact method of reckoning became necessary. This was first afforded by the phases of the moon. These are more obvious to the eye than the annual motion of the sun. At the dawn of civilization, therefore, the moon plays an important part in economic life, and deities of earthly origin have often taken on lunar attributes. The close association of lunar reckoning with the beginnings of civilization is shown by the fact that in Egypt Thoth, at an early date identified with the moon, was credited with the invention of writing and of the calendar. In one text he is even said to have created the world. In Babylonia the moon-god, Sin, was called the "lord of wisdom". Later, as a result of observation by priests who had the necessary leisure to attend to the matter, the tropical year was measured with approximate exactitude. Thenceforth the sun took precedence of the moon and the earth in priestly estimation, and sun-gods became supreme, or older gods were invested with solar attributes. Thus in Egypt Re-Horus became the high god, and Thoth was demoted to the office of scribe.

The process is not completed until civilization is well established, until man has considerable mastery over nature, and until the dependence of the seasons on the sun is an ascertained fact. In spite of this accumulating knowledge, the priesthoods perpetuate traditional rituals of magical origin as a source of power and revenue. Ancient religion is thus an incongruous mixture of magic, totemism, ancestor-worship, nature-worship and rationalizing but contradictory myths -- "deposits of different ages of thought" (and, we may add, of different productive techniques and social relations) "sundered perhaps by thousands of years".7 In these contradictory conceptions successive phases of magic and religion are mingled: the human and mortal magician making rain and multiplying food for his tribe; the totem-species which he impersonated in order to multiply; the legendary ancestor reputed to have taught his descendants magic and useful arts; and the external forces which magic claims to manipulate -- the earth, the rain, the seasons, the moon, the sun -- all going to make the final product, the god. Along with this process goes a widening contradiction between the ideology of the ruling class and the faith of the working masses. Among themselves the Egyptian priests came to regard Re, Horus, Amun, Ptah, Apis, Osiris and the rest as aspects or emanations of one sole being, the source of all life, whom they reasonably (for those times) identified with the sun. But woe to him who undermined their credit with the people by publicly "confounding the persons" and denying the prerogatives of each particular deity! So Pharaoh Akhenaton (1375-1358 B.C.) found to his cost when he tried to thrust aside the priests and suppress all cults but simple worship of the sun's light and power. His revolution perished with him.

Notes1 Frazer, Golden Bough, abridged edition, ch. IV.

2 Alice Fletcher, cited by Jane Harrison, Themis, ch. III.

3 Golden Bough, abridged edition, ch. VII. This may be true even of some palaeolithic societies. Gordon Childe cites the case of artist-magicians among Magdalenian cave-dwellers. What Happened in History, chap. II.

4 Malinowski, Magic, Science and Religion, V, 4.

5 Golden Bough, abridged edition, ch. VII. Cf. Thomson: "The more advanced forms of worship develop in response to the rise of a ruling class -- hereditary magicians, priests, chiefs and kings . . . The idea of godhead springs from the reality of kingship; but in the human consciousness, split as it now is by the cleavage in society, this relation is inverted. The king's power appears to be derived from God, and his authority is accepted as being the will of God." Aeschylus and Athens, chap. I.

6 Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, chap. II.

7 L. R. Farnell, Encyclopaedia Britannica, article Zeus.