Archibald Robertson, The Origins of Christianity, International Publishers, 1954, rev. ed. 1962.

THE BREAK WITH JUDAISM

In 66 the great Jewish revolt against Rome broke out at last. We owe our only detailed accounts of it to Josephus, the rich priest and traitor, whose venom against his countrymen is exceeded only by his admiration of himself. As usual, therefore, with revolutionary movements, the historian has to hew his way through a forest of prejudice to get at the truth.

In common with the whole Empire, Palestine had been drained dry by the misgovernment of Nero. But in Palestine, unlike other provinces, there was a resistance party of long standing capable of leading the masses. The revolt began when the procurator, Gessius Florus, raided the temple treasury to meet unpaid taxes. Since temples in addition to their religious uses served as banks, this forced the wealthier citizens to co-operate in a half-hearted fashion with the resistance. To cow opposition Florus ordered an indiscriminate massacre of the people and scourged and crucified many of them, including some wealthy Jews who happened to be Roman citizens. The rich were now no longer able to control the poor. Driven to desperation, the people fought back, seized the temple, forced Florus to retire to Caesarea and made the priests discontinue the daily sacrifice for the emperor. The economic roots of the movement are revealed by the fact that one of the first acts of its leaders was to burn all records of debt -- " the nerves of the city ", says Josephus with natural bias.1

The priestly nobility made desperate attempts to control the movement which they could no longer prevent. They managed to capture and kill a Zealot leader, a surviving son of Judas of Galilee, named Menahem, who had set up as king. The single cohort left by Florus in Jerusalem surrendered to them on promise of quarter, but were massacred by the Jewish rank and file. Pogroms of Jewish men, women and children in the surrounding Greek cities made surrender unthinkable to any patriot. Cestius Gallus, the governor of Syria, marched on Jerusalem, but was routed with great loss of men and material. The priestly nobility were thus committed to war with Rome whether they liked it or not. Josephus, who was in their counsels and commanded under them in Galilee, admits that they hoped for a speedy Roman victory and were secretly preparing to surrender the country which they professed to defend. In such circumstances it is not surprising that the Zealots, supported by the poorer classes, made a dead set at the priests. After the Roman reconquest of Galilee in 67 (when Josephus seized his chance and ratted to the enemy) the priestly nobility were liquidated without ceremony and the high priesthood filled by lot.

The issue was for a moment in the balance during the upheavals which shook the Roman Empire in 68-69. The same misgovernment which had provoked the Jewish revolt led in 68 to risings in the western provinces and to the downfall and suicide of Nero. For a whole year the Empire was in the throes of civil war. Galba, the commander of the Spanish legions; Otho, put up by the praetorian guard at Rome; Vitellius, the nominee of the army of the Rhine -- all in turn failed to rally enough military support to hold what they had won. The only positive result of this year of chaos was to make many people regret Nero. A few months after the Roman plebs had paraded in caps of liberty in joy at his death, stories were current that he had escaped to Parthia, a false Nero appeared in the Aegean, and Otho was fain to take the name of Nero to legitimate his title. In the end the common interest of men of property throughout the Empire prevailed against the forces of disruption. The legions of the East and the Balkans rallied round Vespasian, the commander in Palestine, and imposed him by force on the distracted West. "The secret had been discovered", says Tacitus, "that an emperor could be made elsewhere than at Rome."

Instead of profiting by the enemy's difficulties, the Jewish leaders wasted time and men in ruinous mutual feuds, apparently expecting that the Roman Empire would collapse of itself. Not until Titus, the son of Vespasian, marched on Jerusalem in April of 70 did they present a united front. Then it was too late. The only Jewish leader who showed some traces of revolutionary statesmanship was Simon Bargiora ("son of a proselyte"), who manned his ranks by offering freedom to slaves and, according to Josephus, was followed with fanatical devotion. While the Jews fought on with lion-like courage, Titus ran up his siege-works, crucified five hundred prisoners a day till "room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses for the bodies",2

and slowly starved out Jerusalem. Thousands -- men, women and children -- perished in August in the conflagration of the temple or were massacred by the Romans in the streets. Thousands were butchered later in gladiatorial shows, and thousands sent to a living death in the Egyptian mines. Simon, the most dangerous leader, was reserved for the triumph of Titus and then put to death.

The last of the Zealots, besieged in 73 in the fortress of Masada, killed their wives and children and then themselves rather than fall alive into the hands of Rome. All land in Judaea was confiscated and sold by auction; and Jews throughout the Empire were made to pay to the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus at Rome the tax which they had formerly paid to the temple at Jerusalem.

2. Christians and the Revolt According to Eusebius and Epiphanius, both fourth-century writers, the Christians of Jerusalem took no part in the national struggle, but migrated before the war to Pella beyond Jordan and were left in peace. That, no doubt, was the story told by the remnant of'the Nazoraean sect to enquirers in the fourth century. But there are reasons for doubting its truth. Pella was raided by the Jews early in the war and would not have been a safe retreat for Jewish deserters. Moreover we know from Josephus that the Essenes took part in the revolt. He names one John "the Essene" among the commanders who fell in the war, and testifies to the bravery of Essene prisoners under torture. As we have seen, the links were very close between Essenes and Nazoraeans. There is evidence that at least some Nazoraeans stayed in Jerusalem during the siege. Josephus says that the defenders were buoyed up to the bitter end by false prophets who promised miraculous deliverance from the Romans. Some of these prophecies seem to have found their way into the Apocalypse of John, though the book as a whole was not written until over twenty years later. In a passage unconnected with its context an angel seals twelve thousand of each tribe of Israel to guarantee their safety in a coming disaster.3 In another fragment the prophet is told to measure the crowded temple with a rod, and informed that the rest of the city up to the outer court will be held by the heathen for forty-two months (reminiscent of the time during which Jerusalem had been polluted by Antiochus over two centuries before). The implication is that the temple itself will be safe.4 This reminds us of a prophet in Josephus who told people to "get up upon the temple, and there they should receive miraculous signs of their deliverance"5 -- with the result that they perished in the flames. Both Josephus and Tacitus mention, as a portent of the fall of Jerusalem, the appearance at sunset of armies fighting in the sky. This too has a parallel in the Apocalypse, but with the difference that the atmospheric phenomenon which Romans and Roman sympathizers interpreted as an omen of their own victory is for the prophet a token of the victory of Israel over the Satanic power of Rome.

"And there was war in heaven:

Michael and his angels warred with the dragon;

And the dragon warred,

And his angels;

And they prevailed not,

Nor was their place found any more in heaven."6In another fragment the Son of Man is seen symbolically reaping the harvest of the earth -- this is, gathering the elect into his kingdom -- and treading the wicked in the "winepress of the wrath of God".

"And the winepress was trodden without the city,an apt description of the condition of Palestine during the Jewish War. Sixteen hundred stadia (nearly two hundred miles) is about the length of Palestine. We shall meet with this simile of the harvest and the vintage again.

And there came out blood from the winepress, even to the bridles of the horses,

As far as a thousand and six hundred furlongs -- "7In another vision the prophet sees Rome as a drunken harlot clad in purple and riding a seven-headed beast, symbolic of her seven hills and of the seven emperors who are to fill up the measure of her iniquity.

"The seven heads are seven mountains,Rome will be devoured by the monster on which she rides and will be burnt to the ground. This alludes to the rumour that Nero had escaped to Parthia and would return to take vengeance on his enemies, and also, no doubt, to the burning of the Capitol by the soldiers of Vitellius in 69. The prophecy must have originated during the chaos following the fall of Nero, but it shows signs of editing.9

On which the woman sits:

And they are seven kings;

The five are fallen,

The one is,

The other is not yet come;

And when he comes, he must continue a little while."8Such passages show that Jewish Christians were not so detached from the national struggle as later tradition made out. The Pauline attitude was naturally very different. To allay the ferment in their congregations due to expectations of the collapse of the Empire, Pauline leaders resorted to an ingenious ruse. Suetonius tells us that astrologers had predicted to Nero in his lifetime that, if driven from Rome, he would reign in the East, and that some expressly promised him the kingdom of Jerusalem. These anticipations clearly belong to the end of his reign. We may be sure that among the wild rumours afloat in 69-70 some connected the fallen Nero with the Jewish revolt. Accordingly a Pauline writer, modelling himself on the genuine letter of Paul to Thessalonica twenty years before and copying the very hand of the apostle, concocted a pseudo-Epistle in which such rumours are cleverly exploited. The "day of the Lord" will not come until after a "man of sin", a "son of perdition", has seduced the Jews and been worshipped as a god in the temple at Jerusalem. This cannot happen until "one that restrains is taken out of the way" -- i.e. until the returning Nero has broken the Roman army in Palestine and installed himself there.10 Meanwhile Pauline Christians are to beware of disorderly people, idlers and busybodies.

It is unlikely that 2 Thessalonians was first published at Thessalonica. Too many there would remember the real Epistle of Paul. The concoction was probably produced in some other Pauline church where it would better serve its purpose. It killed two birds with one stone: it discredited the Jewish rebels by insinuating that they would pay divine honours to Nero, whose atrocities had branded him as the personification of evil; and, by adjourning the "day of the Lord" until after that highly improbable event, it in effect postponed it indefinitely.

3. The Flavian Dynasty

The reigns of Vespasian (69-79), Titus (79-81) and Domitian (81-96) mark a new phase in the history of Roman imperialism. The upheaval which put them on the throne had been due to the over-exploitation of the provinces by the capital. The success of the Flavian family marked a permanent transfer of power from Roman to Italian and provincial hands. They themselves were a banking and tax-farming family from central Italy. They threw the senate open to Italian and provincial notables, bestowed Roman citizenship liberally, and recruited their legions from the provinces where they served. This does not mean that the masses were less exploited; on the contrary, the tribute of the provinces was increased and in some cases doubled. But it went to enrich not only the Roman and Italian owning class, but provincial owners also, and their pampered lackeys in the army.

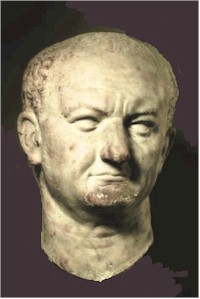

Vespasian

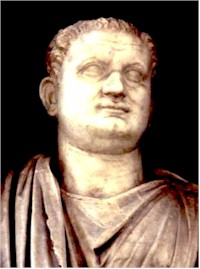

Titus

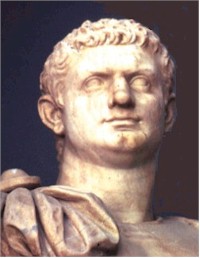

DomitianUnder this systematic and intensified exploitation nothing was left to the masses but dreams. Survivors of the massacre in Judaea escaped to Alexandria, Cyrene and other Mediterranean cities, full of visions of vengeance against Rome, but with no plan of action that could lead to anything but more massacres, tortures and crucifixions. The wealthier Jews were foremost in denouncing these fugitive revolutionaries to the Romans. Josephus reluctantly witnesses to the courage of these people and to their refusal under the extremity of torture "to confess or seem to confess that Caesar was their lord".11

4. The Primitive Gospel Probably these fugitives, fresh from the horrors of Palestine, were the earliest disseminators of what later took shape as the Gospel story. Our existing Gospels have been so edited that its original form is past recovery. But we saw reason in chapter V for thinking that the basis of the Synoptic Gospels was a document written under the immediate impact of the Jewish War and expressing a revolutionary Messianism. Passages in this category are by internal evidence traceable to the primitive Gospel. The catastrophic defeat of the Jewish revolt had to be accounted for. One way of doing so was to represent it as a judgment on the nation for the rejection of a past Messiah, and as the darkest hour before a dawn in which the dead leader would return to set up his kingdom. The rejected Messiah was identified with Jesus the Nazoraean, crucified by the procurator Pilate a generation before the destruction of Jerusalem.

But the primitive Gospel was in no sense a biography of Jesus. It was embellished with incidents which had been related of revolutionary leaders for generations back and had become common form in this class of story, and with teaching which was part of popular Jewish (especially Essene) tradition. Thus it was common form that the Messiah would perform miracles. It was written in the prophets that in Messianic times the blind should see, the deaf hear, the lame leap and the dumb sing. Such stories would be told of any Messianic claimant. And they also served another purpose. Things which could not safely be written in plain language could be put in the form of miracle stories. It was not safe to say openly that the Romans in Palestine would be driven into the sea. But it could be said figuratively. The Tenth Legion, quartered at Jerusalem, had for emblem a boar. By making Jesus send a "legion" of demons into a herd of swine and drive them into the water to drown, the revolutionary lesson is conveyed in symbol to those who "have ears to hear".12 The revolutionary nature of the primitive Gospel is also proved by the fact that, while the Pharisees and Sadducees are denounced, the Zealots are not, and that all lists of the apostles include Simon the "Cananaean" or Zealot.13

Then there are such passages as

"Think not that I cameand

To send peace on the earth:

I came not to send peace, but a sword!"14"From the days of John the Baptist until now

The kingdom of heaven is taken by violence,

And the violent take it by force."15There is the text promising "a hundredfold now in this time" to all who leave house, family or land for the sake of the kingdom;16 the Messianic entry of Jesus into Jerusalem; the expulsion of the money-changers from the temple; the parable summoning the poor to the feast which farmers and merchants have despised; the prophecy that the "wars and rumours of wars" of 66-70 are "the beginning of travail" from which the Messianic kingdom will be born, and that the coining of the Son of Man will be "immediately after the tribulation of those days";17 the reference to "the insurrection" unaccountably left in Mark's story of the Passion;18 the title "king of the Jews" affixed to the cross.19 How many of these incidents actually occurred, or how many of these sayings were uttered by Jesus, is immaterial. Some are clearly invented; some are probably founded on fact. The point is that a Christian writer or writers soon after the year 70 thought them good propaganda. In them the primitive revolutionary Gospel, uninfluenced by Pauline mysticism, pierces through the camouflage of our evangelists.

The primitive Gospel was written in Palestine in Aramaic at the time of the Jewish War, and turned into Greek by revolutionary propagandists in the Mediterranean cities to which they made their way. This accounts for the occurrence of Aramaic words and phrases in the existing Gospels. The use of Aramaic phrases would have served no useful purpose in a work originally written for a Greek-speaking public; but they are intelligible if the basic document was Aramaic. This evidence tallies, so far as it goes, with the statement of Papias in the second century that "Matthew collected the oracles in the Hebrew language, and everyone translated them as best he could".20

5. Primitive Church Organization We get a glimpse of the communities for which the primitive Gospel was written in a handbook of instruction compiled in Syria late in the first or early in the second century and entitled The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles. The first part of this is based on a Jewish tract addressed to Gentile converts and probably entitled The Two Ways. This part contains no reference to Christianity. It contrasts the "way of life" (true religion, neighbourliness, chastity, honesty, sincerity, open-handedness) with the "way of death" (idolatry, lewdness, hypocrisy, duplicity, greed and oppression of the poor). In it occur (or have been inserted) passages so closely similar to passages in Matthew and Luke that at first glance they seem to be based on the Gospels. But on closer inspection the differences are as striking as the resemblances. The tone of the Teaching is more opportunist and less dogmatic than that of the Gospels. Thus, where Matthew and Luke have "Love your enemies",21 the Teaching has "Love them that hate you, and you shall have no enemy."22 Where Luke says, "Of him that takes away thy goods ask them not again,"23 the Teaching gives a reason: "If anyone takes from thee what is thine, ask it not back; for indeed thou canst not."24 Where Matthew has, "Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth,"25 the Teaching is more frankly opportunist: "Be meek, since the meek shall inherit the earth."26 Further, while the Synoptics attribute all these sayings to Jesus, the Teaching cites no authority. In fact, the Teaching takes us back behind the canonical Gospels to a time when submission to the Roman conqueror was a counsel of prudence, but not yet represented as the command of Christ.

The second part of the Teaching is wholly Christian, but shows no trace of Pauline doctrine. Most of it cannot be much later than the beginning of the second century, and some of it may be earlier. The Lord's Prayer is given substantially as in Matthew, and is probably taken from the primitive Gospel. The eucharistic formula is unlike any in the New Testament and contains no reference to the Last Supper. In the Teaching, as in the Pauline Epistles, the eucharistic bread and wine are part of a common meal at which church members eat and drink their fill. But in the Teaching bread and wine do not in any way symbolize the body and blood of Christ. The Christ of the Teaching is not a god, a projection of the Christian community, but a "servant" of God by whom "life and knowledge, . . . faith and immortality" have been made known to men. The Teaching does not mention the crucifixion: its readers are less interested in the sufferings of the Messiah than in his coming triumph. The bread which as growing corn was "scattered over the hills", but has been baked into a loaf, symbolizes the assembly of God's people from the ends of the earth into his kingdom.27 What the wine symbolizes we are not told, but we can guess if we compare the Teaching with the Apocalypse of John. There, as we saw, the reaping of the harvest represents the deliverance of the elect, and the treading of the vintage the destruction of their enemies. The danger of committing such matter to writing explains why the Teaching is silent on the symbolism of the cup.

In the last part we get a picture of day-to-day life in Christian organizations. As in the Pauline churches, the key people are travelling missionaries or "apostles" (not confined to the traditional twelve) and preachers or "prophets". So long as they conform to the teaching in the handbook, they are to have a free hand and are not to be interrupted or heckled. But apostles are not to stay in the same place more than one or at most two days. They are allowed subsistence for their journey to the next place of call, but are not to charge fees. Resident preachers and teachers are allowed maintenance, but not money payment. Careerists ("Christmongers") are sternly denounced. The common meal is held every Sunday, quaintly called "the Lord's day of the Lord", since there were other "Lord's days" sacred to pagan gods.28 There is no indication that Sunday was kept as the day of the resurrection. The pagan "day of the sun" was consecrated to the Christian common meal because it was already a festal day in the circles in which converts were made; the Gospel stories of the resurrection came later.

The affairs of each church are managed by local officials ("bishops" or overseers, and "deacons" or helpers) who are democratically elected, and who also preach and teach; but their functions are dismissed in two sentences. Evidently "apostles" and "prophets" were more important.

The Teaching ends with an exhortation to vigilance. Evil days are at hand, when false prophets will abound, and a "world-deceiver" (the returned Nero) worshipped as a god will rule the earth and "commit iniquities which have never yet been done since the beginning. Then all created men shall come into the fire of trial, and many shall stumble and perish. But they that endure in their faith shall be saved." Then the heavens shall open, the trumpet shall sound, the dead saints shall rise, and "the world shall see the Lord coming upon the clouds of heaven".29

The Teaching is not the work of one hand or one time, but it is good evidence for the character of the Christian movement in Syria late in the first and early in the second centuries. Essentially it was a breakaway Judaism. The Teaching is adapted from a Jewish pamphlet. Jesus is the Messiah and the servant of God, but not himself God. The Pauline idea of Christ as the indwelling spirit of the Christian community is totally absent. Submission to the oppressor is urged on grounds of expediency, but is not cited as the command of Jesus. Week by week the faithful pray for, and celebrate in symbol, the speedy coming of the kingdom of God, when his will shall be done on earth as in heaven, his people shall be gathered in, and his enemies shall be trampled in the winepress of his wrath.

The Teaching circulated mainly in Syria and Egypt. The primitive Gospel, originating in the same area and written in the same spirit, had a far wider circulation and caused far more anxiety to the Paulinists who were striving to inoculate the masses against revolutionary propaganda. When the posthumous eulogist of Paul who wrote 2 Corinthians x-xii referred to Messianists "according to the flesh" who preached "another Jesus, whom we did not preach",30 no doubt he had in mind the disseminators of the Gospel of a revolutionary Messiah, so different from the spiritual Christ of Paul and so dangerously attractive to the disinherited classes of the Mediterranean world.

6. The Roman Gospel To counter such propaganda Pauline Christians needed a Gospel of their own. The first essay in this direction was the Gospel of Mark, the original edition of which was written some few years after the suppression of the Jewish revolt, when the primitive Gospel had reached Rome and was causing a stir there. There is no reason to doubt that the author of our Second Gospel was the Mark who figures in early Christian tradition as a companion sometimes of Peter and sometimes of Paul. In the Pauline Epistles Mark is a cousin of Barnabas, a fellow-worker of Paul and one of his companions during his imprisonment at Rome.31 In 1 Peter (a spurious Epistle, but good evidence for the tradition current early in the second century) Mark is represented as a close companion ("son") of Peter on his mission to Rome ("Babylon").32 The Acts tell a longer story. "John, whose surname was Mark," comes from Jerusalem, where his mother is known to Peter and is apparently a person of property, since the church meets in her house. Mark, therefore, is not one of the "poor saints". He accompanies Paul and Barnabas on their mission to Cyprus, but leaves them when they proceed to Asia Minor. As a result Paul refuses to take him on a second mission and quarrels with Barnabas. Mark then goes with Barnabas to Cyprus and drops out of the narrative. The Epistles nowhere allude to the mission to Cyprus or to the desertion of Mark. The story may be a romance of the author of the Acts designed to disparage a rival evangelist. Papias, writing about 140, is the last authority whose account of Mark is worth recording. He tells us that he had heard from an unnamed "elder" that Mark was not a disciple of Jesus, but was Peter's interpreter and wrote "accurately, but not in order", what Peter had related of the sayings and doings of Jesus.33

No doubt Mark had had relations of some sort with Peter, and certainly with Paul. But Papias' account of the origin of his Gospel must be rejected. It is a Pauline, not a Petrine work, and it is based not on personal reminiscences -- least of all on Peter's -- but on variant versions of an earlier Gospel freely rehandled. Thus the feedings of the five thousand (Mark vi, 31-44) and the four thousand (viii, 1-9) -- both in a "desert place" and both with a few loaves and fishes -- are obviously variants of a single story told to explain the origin of the Christian common meal. The disciples are just as helpless on the second occasion as on the first; and there is no hint that the same situation has arisen before. Each miracle is followed by a clash between Jesus and the Pharisees (vii, 1-13; viii, 11-12) and by a miraculous cure (vii, 32-37; viii, 22-26) on which Jesus enjoins silence. Evidently the story reached Rome in two versions. Mark inserts both and adds a paragraph in which Jesus rebukes the stupidity of his disciples (viii, 14-21).

Mark's object is to remodel the Jesus of the primitive Gospel in the image of the Pauline Christ and thereby to draw the sting of revolutionary Messianism. In Mark, Jesus becomes Son of God through the divine Spirit descending on him at his baptism and endowing him with power over demons, disease and death. Faced by this phenomenon, the countrymen, kindred and even disciples of Jesus are completely at sea. His friends say that he is mad. His mother and brothers (who know nothing of the virgin birth of later legend) try to contact him and are bluntly told that

"Whoever shall do the will of God,

He is my brother and sister and mother."34Mark has an answer ready for those who claim to quote against him the actual teaching of Jesus. That teaching, says he, consisted of parables which the multitude were not meant, and which the twelve were too stupid to understand. It was for those who had "ears to hear".35 Mark suppresses the primitive material (preserved in Matthew and Luke) on the good time coining for the poor and hungry, the impossibility of serving God and Mammon, the taking of the kingdom of God by violence, the exaltation of the low and the humiliation of the high. It is usual to trace this material to a separate document, which modern scholars call Q from the German Quelle, "source". But there is no reason to think that Q ever existed as a document. Q is simply that part of the primitive Gospel which Mark as a Pauline Christian deliberately suppressed.

The only occasions when Jesus, in Mark, speaks plainly to the multitude are when he proclaims the Pauline doctrines of the nullity of Jewish food taboos and the indissolubility of marriage. Both these have to be explained over again to the dense disciples. Peter in a lucid moment recognizes Jesus as the Christ, but immediately spoils it all by "rebuking" him for prophesying his death and resurrection; whereupon Jesus turns fiercely on Peter with: "Get thee behind me, Satan!"36 (We remember how in 2 Corinthians xi the "pre-eminent apostles" are denounced as ministers of Satan.) The twelve go from stupidity to stupidity and from cowardice to cowardice. The transfiguration reduces Peter to gibbering imbecility. They dispute over their precedence in the Messianic kingdom and end by running for their lives, while Peter thrice denies Jesus. All this is not biography or history, but the counter-propaganda of Mark, the fellow-worker of Paul, to the Palestinian gospel of revolution. It is hard to believe that Mark had ever been intimate with Peter, whom he depicts in so contemptible a light. In order to dissociate Christians from any subversive activity he deliberately shifts the responsibility for the crucifixion from Pilate to the Jews -- an audacious fiction which later evangelists underlined in every possible way.

Mark is a careless writer. In revising the primitive Gospel he lets details stand, such as the limitations of the healing power of Jesus, which are hard to reconcile with the thesis that Jesus was the vehicle of the divine Spirit; and others, such as the "legion" miracle (v, 1-20), the promise of earthly rewards (x, 29-30), the Messianic entry into Jerusalem (xi, i-io) and the allusion to "the insurrection" (xv, 7) which reveal the revolutionary character of the real movement. The genuine part of Mark ends at xvi, 8, with the women flying from the empty tomb and saying "nothing to anyone; for they were afraid". But he cannot have ended so. Whatever he said about the risen Christ was so unacceptable to second-century Christians that they deleted it and substituted verses 9-20, which are a mere condensation from the Third and Fourth Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. Some fourth-century manuscripts lack this ending.37

Gospel-making was an important instrument in the gradual fusion of Pauline and Jewish Christianity. The Pauline propaganda of the middle of the first century had opposed to revolutionary Judaism the idea of a wholly spiritual Christ whose kingdom was not of this world, who shared the sufferings of his votaries and who gave them victory over death. This propaganda failed in its immediate object. The gospel of an actual Messiah who had suffered on a Roman cross, but would return and set up the kingdom of God on earth, had a greater mass appeal -- the greater because the recent deaths of so many revolutionaries on Roman crosses cried aloud for vengeance. The Paulinists had therefore to de-Judaize the historical Jesus, to refashion him as a mystery-god and so to transfer the kingdom of God from earth to heaven. This was the work of the later Gospel-makers.

7. Domitian and the Jews The process was hastened by the repression of Judaism under the Flavian emperors and especially under Domitian. The Jewish War had forced into the open the antagonism which had always existed between Judaism, with its dream of a kingdom of God on earth, and the existing Graeco-Roman social order. Under Domitian not only was conversion to Judaism forbidden on pain of death or confiscation of goods, but (says Suetonius) "those were prosecuted who, without publicly acknowledging that faith, yet lived as Jews, as well as those who concealed their origin and did not pay the tribute levied upon their people".38 Converts to Christianity could escape Domitian's inquisitorial net only by a total repudiation of Judaism and its obligations. Since the hope of a kingdom of God on earth was the root from which the Christian movement had stemmed, very few Christians were ready for such a total repudiation. In the primitive Gospel:

"Till heaven and earth pass away,In the less rigid Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, which circulated in Syria and Egypt, the Jewish law is the ideal to which converts are to conform as far as they can. "If thou art able to bear the whole yoke of the Lord, thou shalt be perfect; but if thou art not able, what thou art able, that do."40 The crucial question for Christians under Domitian was how much of Judaism they could jettison without ceasing to be Christians.

One jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass away from the law."39One of the chief centres of Jewish revolutionary agitation and anti-Jewish repression was Alexandria. At Alexandria about this time appeared an anonymous Christian tract commonly known as the Epistle of Barnabas.41 The author pleads for the total repudiation by Christians of the Jewish law. Outdoing Philo in the allegorical interpretation of scripture, he contends that the Pentateuch was never meant to be taken literally, and that the Jews misunderstood it from the first. In proof he cites the invectives of the ancient prophets against the temple cult. The "land flowing with milk and honey" is not Palestine, but (by a freak of interpretation) Jesus Christ -- "land" symbolizing a man (since man is made of earth) and "milk and honey" the Christian faith. "Circumcision" means not the Jewish initiation rite, but circumcision of the "heart" by hearing and believing. Food taboos mean not abstinence from particular meats, but abstinence from the vices typified by various animals. Here the author introduces some odd bits of popular zoology. The building of the Jewish temple was a sin justly punished by its demolition. The true temple is in the hearts of Christian believers. The Messiah is not, as pretended by the Jews, a Son of Man, much less a Son of David. The twelve apostles were "sinners above all sin". In this the author outdoes Mark, who makes the twelve out fools, but stops short of calling them knaves. The author ends (notwithstanding his anti-Judaism by citing, in a slightly different form, the Jewish tract on the Two Ways which is also used in the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles. Owing to its extreme anti-Judaism the Epistle of Barnabas seems never to have circulated much outside Alexandria and, though found in some manuscripts, did not eventually win its way into the . canon of the New Testament.

8. The Apocalypse How hard it was to cut the Jewish roots of Christianity may be gathered from the popularity among Christians of the most Jewish book that ever found its way into the New Testament. About 93-95 a Jewish Christian in Asia Minor, probably one who had escaped from Palestine twenty years before, collected some prophecies (possibly his own) dating from the Jewish revolt, added much new matter and produced the poem known as the Apocalypse (or Revelation) of John. Jewish apocalypses were invariably pseudonymous; and there is no reason to think that the author had anything to do with John the apostle.42 He uses the name for intelligible reasons to conceal his own identity. He was not a native of any of the Greek cities of Asia Minor to which his work is addressed; for he writes Greek as a foreign language which he has never mastered.

Anyone familiar with the prophetical books of the Old Testament can see that the visions of the Apocalypse are a literary artifice and not the record of a personal experience. Its themes and its very language are taken wholesale from the Hebrew prophets. To collect such in material was easy to anyone soaked in the older prophetic literature. But into this mould of stock prophetic imagery the writer pours a wealth of white-hot invective which could have come only from a Jewish revolutionary under the Flavian emperors. He is brimful of hate against Rome and against the Pauline missionaries who preach submission to Rome.

The first part of the Apocalypse consists of seven short epistles (as we should say, open letters) to Christian congregations in Asia Minor which had once been a stronghold of Paulinism, but which had become a scene of furious conflict. Writing in his ungrammatical Greek, he congratulates the churches of Ephesus, Smyrna and Philadelphia on having seen through the false apostles and false Jews, the "synagogue of Satan".43 But in some churches the Paulinists are harder to evict. At Pergamum they are in a strong position. At Thyatira they are led by a woman preacher or "prophetess" whom the author fiercely denounces as "Jezebel".44 Evidently the embargo on women preachers, later inserted in the Pauline Epistles, was not yet in force at the time of the Apocalypse. But "Jezebel" leads a minority only. The majority are commended for rejecting "the deep things of Satan" -- a parody of the phrase, "the deep things of God", used by Paul of his own teaching.45 The worst marks are awarded to the church of Sardis, which is "dead",46 and to that of Laodicea, which the Messiah will "spew out of his mouth" as "neither cold nor hot".47

After this the seven churches drop out of the poem. The transition is so abrupt that it is reasonable to regard the letters to the churches as a later insertion in the work. But if so, the insertion is the writer's own. The uniformity of language, even down to mistakes in grammar, establishes unity of authorship.

The author's ideas of the "kingdom of God" are as materialistic and un-Pauline as they can be. The Messiah, symbolized in the poem by a slain Lamb -- a projection and personification of the martyrs of all ages, "slain from the foundation of the world"48 -- has purchased by his blood an earthly kingdom for "men of every tribe and tongue and people and nation".49 The redeemed are to be kings and priests: the author recognizes no hierarchy within the movement. But before that kingdom comes, tribulation stalks the earth. Four horsemen (taken from Zechariah) carry war, famine and pestilence to mankind. Corn soars in price, while the luxuries of the rich abound.50 Jerusalem is trodden under foot by the Gentiles. During this time the beast-empire of Rome -- the very incarnation of Satan -- led by a returned Nero slays those who will not worship his image. Nero is cryptically identified by the number 666 -- the sum of the numerical values of the letters of "Nero Caesar" in Hebrew. False Neros had appeared in the eastern provinces in 69, in 80 and again in 88. But to many, and. perhaps to our prophet, Domitian himself with his cruelty and his assumption of the title of "Lord and God" ("names of blasphemy" in Christian eyes)51 seemed Nero enough to fill the bill.

In any case the days of Antichrist are numbered. Angels flying in mid-heaven proclaim that the hour of judgment is come, that "Babylon the great" (Rome) is fallen, and that emperor-worshippers will be tormented for ever with fire and brimstone. The prophet's ferocity, revolting if read out of its historical context, is a natural retort to the ferocity with which the Flavian emperors had treated the conquered Jews. Plagues of boils, of blood, of scorching heat, of supernatural darkness, recalling those of Egypt in Exodus, rain on the Roman Empire amid angelic acclamations.

"I heard the angel of the waters saying,

'Righteous art thou,

Who art and who wast, thou holy one,

Because thou didst thus judge:

For they poured out the blood of saints and prophets,

And blood hast thou given them to drink:

They are worthy.' "52Parthian armies invade the stricken Empire and burn Rome. A hymn of hate celebrates the fall of the harlot city with her merchants, mariners and client kings.

"The merchants of the earthTraffic in human beings crowns the prophet's indictment.

Weep and mourn over her,

For their cargoes

No man buys any more;

Cargoes of gold and silver and precious stone and pearls,

And fine linen and purple and silk and scarlet;

And all thyine wood, and every vessel of ivory, and every vessel of most precious wood,

And of bronze and iron and marble,

And cinnamon and spice and incense and ointment and frankincense,

And wine and oil and fine flour and wheat,

And cattle and sheep; and of horses and chariots and slaves,

And souls of men."53With Rome a smoking ruin, the kingdom of God is inaugurated on earth. The Messiah, a warrior in blood-stained garments, leads the armies of heaven to annihilate his foes. The beast-emperor is cast into hell; and the birds of the air fatten on the flesh of his armies. For a thousand years the faithful will live and reign with the Messiah in Jerusalem. At the end of the millennium the prophet, following Ezekiel, foresees a last war between the saints and new enemies from the ends of the earth, and a last supernatural victory. Then the last judgment of the dead, when cowards, traitors and idolaters will join Nero in hell; and then a new heaven, a new earth and a new Jerusalem in which God shall dwell with men, and death, mourning and pain shall be no more. The author's Utopia, though miraculous, is earthly and material to the end.

The end of the Apocalypse, like the beginning, has been rehandled. The new Jerusalem descends from heaven to earth twice, in xxi, 2, and in xxi, 9-10. In xix, 10, the seer falls down to worship the angel who shows him the vision, and is rebuked; in xxii, 8-9, the same mistake provokes the same rebuke. Obviously, therefore, the section beginning at xxi, 9, is not a continuation, but an alternative version of what immediately precedes it. It looks as if the author had rewritten this part in a second edition, and as if a later editor, finding two versions current, had combined them regardless of repetition. The account of the new Jerusalem, like the rest of the Apocalypse, is an echo of ancient prophecies, especially those of Ezekiel and the Second Isaiah. The author in his second edition seems to take a less ferocious view of the destiny of the Gentiles. The gates of the new Jerusalem are open to all except idolaters, sorcerers, murderers and the like; by the riverside grow trees bearing fruit every month; and "the leaves of the tree" are "for the healing of the nations".54

The popularity of the Apocalypse is proved not only by the issue of two editions by the author himself, but by its early acceptance as a canonical book. Papias cited it as authoritative in the first half of the second century. Justin in the middle of the century, in spite of his pro-Roman attitude, accepts the Apocalypse as the work of John the apostle. But as time went on the book proved embarrassing to Church leaders who sought accommodation with the Roman Empire. Not only Marcion, an exponent of extreme anti-Judaism, but other second- and third-century writers denied its authority. Some went so far as to ascribe it to Cerinthus, a prominent Jewish Christian at the end of the first century, whose doctrine of a material millennium was obnoxious to the Greek Fathers; and the attribution is not impossible. Eusebius in the fourth century hesitates whether to class the Apocalypse among canonical or spurious books. Its place in the canon was eventually secured by the support of the mass of Christians who, whatever scholars and courtiers might say, found its invective against the rulers of the earth and its prophecy of a material millennium exactly to their taste.55

9. The Epistle to the Hebrews Paulinists were trying to wean the Christian movement from dreams of revolution. This could not be done by totally repudiating Judaism, but only by reinterpreting it and proving that it contained prophecies of its own supersession. That is the line taken in an anonymous tract published at Rome about this time, entitled in our Bibles the Epistle to the Hebrews and attributed, in the teeth of internal and external evidence, to the apostle Paul. It is an epistle in name only. Apart from a few verses tacked on to the end to give it the look of a letter, it has no resemblance to one: it bears no name and no indication of its addressees. It was first attributed to Paul at the end of the second century at Alexandria, probably for no better reason than to find an apostolic author for a highly esteemed piece of writing. Tertullian, writing about the same time at Carthage, attributes it to Barnabas. But the work clearly belongs not to the first, but to the second generation of Christians. At Rome, where it first appeared, its Pauline authorship was denied down to the fourth century. At Rome today that denial is heresy.

The Epistle to the Hebrews is an exposition by a Pauline Christian to other Pauline Christians (not necessarily Hebrews) of the relation of Christianity to Judaism. The work is in good literary Greek -- the best in the New Testament -- and its addressees seem to be people of means and education. Under the pressure of Domitian's inquisition they are in danger of apostasy to paganism. The author's object is to stiffen their morale. He reproaches them with requiring instruction when they ought to be instructing others. He tells them that Christianity is not the negation of Judaism, but the substance of which Judaism is the shadow. To prove this he appeals to the Old Testament, which he twists in a way that was to become increasingly common as the breach between Christianity and Judaism developed. After the manner of Philo he ransacks the Psalms, the prophets and the Pentateuch to establish conclusions at which their authors would have gaped -- the divinity and incarnation of Christ, and the supersession of the Jewish cult by his sacrifice of himself. In a typical piece of Philonian allegorizing the author uses the myth of Melchizedek, to whom in Genesis Abraham gives a tenth of the spoils of victory, to prove the superiority of Christianity to Judaism. Consequently apostasy is not less, but more heinous in Christians than in Jews; indeed it is past pardon. The author rejects an earthly millennium. Unlike the heroes of old who fought for an earthly Israel, Christians desire "a better country, that is a heavenly".56 He exhorts them not to abandon their meetings, "as the custom of some is"; to "call to remembrance the former days" (those of Nero's persecution); and to resist apostasy, as they have not yet done, to the death.57

From the reiterated warnings of this writer against apostasy it is evident that with middle-class Christians morale was a serious problem. They did not share the heartfelt hatred of the Empire which animated the poorer Messianists. There was real danger that they would fail in the hour of trial. To prevent that the Epistle to the Hebrews was written.

10. End of the Flavian Dynasty Domitian's persecution of Jews and Christians cost him dear. He had made the mistake of fighting on two fronts. The power of the Flavian dynasty, as we have seen, depended on the support of the owning classes of the Empire as a whole. Domitian failed to understand this, and became involved in a feud with the senate at the very time when he was posing as the protector of Roman institutions against subversion from below. Exploiters and exploited, senators and small men found themselves the victims of a common tyranny. This brought certain highly placed Romans into touch with the Christian movement. In 95 Domitian put to death a senator named Acilius Glabrio on a charge of plotting revolution. It is singular that in one of the catacombs used as burying-places by the early Christians there should be fragments of the epitaphs of several Acilii, including an Acilius Glabrio. Evidently many of the family were Christians; and the revolutionary senator may have been among them. In the following year, 96, Domitian executed his own cousin Flavius Clemens, an ex-consul, and banished Flavia Domitilla, the wife of Clemens, on a charge of "atheism and Jewish practices".58 There is no room for doubt that they were Christians. The oldest of the catacombs is proved by its inscriptions to have lain in ground belonging to Flavia Domitilla. Eight months later Domitian was assassinated in his bedchamber by the steward of Domitilla, Stephanus, and some accomplices. One Christian at least -- and she a woman -- was no non-resister!

Flavius Clemens is probably the only real person behind the shadowy figure of "Clement of Rome". Shortly before, or perhaps shortly after the death of Domitian the Roman church addressed a letter to the Corinthian church on questions of discipline. There is no internal evidence of authorship; and the fact that the letter bears no name is proof positive that at that time no single bishop, and therefore no Pope was at the head of the Roman church. The name of Clemens (Clement) seems to have been attached to the letter late in the second century for no better reason than that he was known to have been prominent in the Roman church about the date when it was written, and had been enrolled in the spurious list of "bishops of Rome" (beginning with Peter) composed later on.

The main interest of the Epistle lies in the light it throws on church organization at the end of the first century. As we have seen, the earliest churches had no clergy in our sense of the word. "Spiritual gifts" such as preaching or teaching could be exercised by any church member, man or woman. "Bishops" and "deacons" (literally, overseers and helpers) were elected officials of the local church. But, by a process not unfamiliar to us, elected officials came in course of time to consider themselves entitled to continuity of office. About 95-96 a party in the Corinthian church dismissed several of their "bishops". We do not know why; but we know that at that time a struggle was raging between the Jewish and Pauline parties in the neighbouring churches of Asia Minor, and we may guess that it had repercussions at Corinth. Perhaps a rank-and-file movement, fired by the millennial hopes of the Apocalypse, revolted against grey-bearded elders who had known Paul. The beaten party at Corinth appealed to the Roman church; and this Epistle is the reply.

The writer uses good literary Greek and is evidently a man of education. After apologizing for delay in answering, due to "the sudden and repeated calamities and reverses which have befallen us" (Domitian's persecution), he vehemently supports the dismissed officials. He deplores the "detestable and unholy sedition" of "a few headstrong and self-willed persons" which has disrupted the church of Corinth.59 The young are to obey their elders. Jealousy and envy have wrought evil from, the beginning of the world, and in Nero's persecution brought about the martyrdom of Peter and Paul. This, as we saw in the last chapter, is the earliest evidence we have of the fate of Peter and Paul, and the first attempt at a posthumous reconciliation between the rival apostles.60 The writer cites a few "words of the Lord Jesus", enjoining mercy and forgiveness, from a source unidentifiable with any known Gospel. He knows and cites I Corinthians and the Epistle to the Hebrews (naturally, since it had lately appeared in Rome) but no other writing of the New Testament. With something like Roman pride he refers to the discipline of the legions as an example of that which should prevail in the Church.61

"Let us mark the soldiers enlisted under our rulers, how exactly, how readily, how submissively they execute the orders given them. All are not prefects, nor tribunes, nor centurions, nor captains of fifty and so forth; but each man in his own rank executes the orders given by the emperor and the governors. The great cannot exist without the small, nor the small without the great . . ."So in our case let the whole body be saved in Christ Jesus, and let each man be subject to his neighbour, according as he was appointed with his special grace. Let not the strong neglect the weak; and let the weak respect the strong. Let the rich minister aid to the poor; and let the poor give thanks to God because he has given him one through whom his wants may be supplied."62

He then lays down what was to become known as the doctrine of apostolic succession. Christ appointed the apostles; the apostles appointed bishops and deacons to succeed them and provided that "other approved men" should succeed these. Bishops and deacons, provided their conduct is good, are not to be "thrust out".63 This is the first assertion in Christian literature of the irremovability of the clergy. It is flatly contrary to the freedom of election recognized in the Teachingg of the Twelve Apostles. It is significant that the only proof of his statements offered by the writer is from the Old Testament. He comparers the Corinthian rebels to the Israelites who mutinied against Mosses and Aaron, and to the persecutors who threw Daniel to the lions andd his three friends into the fiery furnace! He calls on them either to submit or to quit Corinth, that "the flock of Christ" may "be at peace with its duly appointed elders".64

This Episistle is an example of the combination of social conservatism, loyalty to the Roman Empire and an authoritarian view of church government which had become the policy of the Pauline party. History was is on their side. The result of the Jewish War had proved revolt against Rome to be hopeless and forced revolutionaries to take refugee in dreams and fantasies. Domitian's prohibition of conversion to Judaism drove a permanent wedge between the church and the synagogue. The leading Jewish rabbis, living on Roman sufferance at Jamnia in the coastal plain of Palestine, abandoned propaganda and gave themselves up to those scholastic studies of the law and the prophets which later produced the Mishnah and the Talmud. Revolutionary propaganda like the Sibylline Oracles and the apocalypses of Enoch, Baruch and Ezra still circulated, but found no favour with the rabbis. These Jewish apocalypses owe their preservationn to Christian copyists and translators, and survive today only in Greeek, Latin, Syriac, Ethiopic or Slavonic texts. Yet, with the single exception of the Apocalypse of John, no such work has found its way into the New Testament. The Christian rank and file might cherish writings which prophesied the fall of world-empires and the advent of the millennium. Their leaders were set on reconciliation with Rome and on the diversion of hopes of redemption from earth to heaven.

This proocess was assisted by economic factors. Revolutionary propaganda naturally appealed most to the poorest classes—the "poor saints" of Palestine for whom Paul had collected money from his churches; the debtors, vagabonds and runaway slaves who, Josephus says, had flocked to the standard of the Jewish rebels; the Jews of Rome whose penury made them a butt of satirists like Juvenal: and such of the poorer Gentiles as could be won by visions of a millennium founded on the ruins of fallen "Babylon". Such propaganda might have mass appeal, but could command no money. Pauline propaganda on the other hand, though equally addressed to the masses, had from the first moneyed supporters -- Paul himself, from whom the greedy Felix had hoped for a bribe; Lydia, the seller of purple whom Paul converted at Philippi; Stephanas of Corinth, "Erastus the treasurer of the city",65 and other affluent Greeks who contributed to Paul's funds; Philemon of Colossae, to whom he sent back a runaway slave; and, a generation later, the addressees of the Epistle to the Hebrews, who "ministered to the saints and still do minister".66 Money, leisure and organizing experience were more likely to be found among Pauline than among Jewish Christians. Once the Paulinists had put their funds and power of organization at the disposal of the poorer Christians, and had proved their equal title to the Christian name by resisting the emperor-worship exacted by Domitian, their control of most of the churches (and of the disbursement of benefits and admission to, or exclusion from, the common meal, which went with that control) was a matter of time. Once in control, they naturally favoured a system of church government which would prevent the rank and file getting out of hand as they had done at Corinth.

The death of Domitian gave them a few years of quiet in which to work. Nerva, his successor, revoked his repressive edicts. Pauline leaders could reasonably hope that, if they restrained their fellow-Christians from revolutionary action, they might enjoy at least an equal toleration with the Jews, who had not long since been in open rebellion against the Empire; and at Rome at least they seem at this time to have received it. Under Nerva and in the early years of Trajan proceedings against Christians were so rare that, when the younger Pliny became governor of Pontus and Bithynia in 111, he did not know how to deal with Christians and had to write to Trajan for guidance.

11. The Syrian Gospel The literature of the churches had to be rewritten to meet the new situation. As we have seen, the only Gospels which can be proved to have existed in the first century are, firstly, an Aramaic work attributed to the apostle Matthew and written under the immediate impact of the Jewish revolt -- a manifesto of revolutionary Messianism, looking for the speedy advent of the kingdom of God on earth and circulating only in the Aramaic-speaking churches of Palestine and Syria; secondly, Greek documents purporting to be translations of this and circulating in the chief Mediterranean cities; and thirdly, Mark's Gospel, written at Rome as a Pauline counterblast to this, deliberately suppressing its revolutionary message and depicting Peter and company as dolts who had misunderstood Jesus and had finally forsaken him and fled.

All such documents were subject to interpolation. There was no central authority yet to declare one writing canonical and another apocryphal. Such partisan pamphlets could hardly serve as manuals of instruction in churches containing both Pauline and Petrine Christians. The rival versions had to be harmonized. The posthumous reconciliation of Peter and Paul had to be completed.

The work was done independently in different parts of the Empire. In the early years of the second century a Syrian Christian dovetailed the Jewish Matthew with the Pauline Mark, and produced for the Greek-speaking churches of the East what we know as the "Gospel according to Matthew". The Jews were numerically strong in the East; and Jewish Christians still predominated in the eastern churches. The primary aim of our First Gospel is to wean such people from their Jewish background. The result is a strange patchwork in which the author combines contradictory sources without much intelligence. His Jesus is a Jew, "the son of David, the son of Abraham",67 but also the Pauline Son of God. From the primitive Jewish Gospel the evangelist takes long discourses said to have been addressed by Jesus to the Jewish multitude -- including such sayings as that not a jot or a tittle of the law shall pass away till all things are accomplished, and that the teaching of the scribes and Pharisees is to be followed, but their practice avoided. From this source too are taken the charge to the twelve not to preach to the Samaritans or the Gentiles, and the prophecies that they will not have gone through the cities of Israel before the Son of Man comes, and that the advent will immediately follow the horrors of the Jewish War. At the same time, without any apparent sense of incongruity, our evangelist reproduces the Pauline Mark's statements that Jesus abrogated the Jewish sabbath and dietary rules, that he spoke to the multitude in parables to conceal his meaning, and that the gospel is to be preached to all nations before the end comes. Our evangelist reproduces Mark's disparagement of Peter -- his stupidity, his cowardice, his denial -- but to conciliate Petrine Christians balances this with the famous pun in which Peter is proclaimed the "rock" on which the Church is built, and is promised the "keys of the kingdom of heaven".68 This passage, by the way, has nothing to do with the Roman church, of which Peter was not regarded as the founder until much later.

These contradictory accounts are juxtaposed without any attempt at reconciliation. Sometimes the evangelist meets with variant versions of the same story -- e.g., of the Gadarene miracle and of the blind man cured at Jericho. In such cases he duplicates the miracle and gives us two Gadarene demoniacs and two Jericho cures. Anti-Jewish polemic takes the form largely of quotations from the prophets -- usually forced and sometimes careless. Occasionally the writer's zeal to make an anti-Jewish point leads to absurdity, as in the parable of the wedding guests. Originally (as we can see by comparison with Luke) this was a simple allegory of the rejection of the Messianic message by the rich and its acceptance by the poor. But our author must at all costs drag in the destruction of Jerusalem. So in his version of the parable the guests murder the messengers sent to fetch them, the host (who in this Gospel is a king) sends an army to burn their city, and the feast proceeds with new guests, the interval for military operations not having spoilt the cooking!69

With all its naiveties and contradictions, this Gospel is invaluable for the early material which it preserves and which reflects "in a glass darkly" the revolutionary character of primitive Christianity. From this material we know that John the Baptist and Jesus the Nazoraean were regarded by their followers as prophets of the "kingdom of God" proclaimed in Daniel, which was to break in pieces all earthly empires and to stand for ever. The commentary on the law put into the mouth of Jesus corresponds with the teaching of the Essenes, whose revolutionary role, minimized by Josephus, is now no longer deniable. By comparing different Gospels we can see how this teaching was watered down -- how the poor became the "poor in spirit";70 how the hungry became "they that hunger and thirst after righteousness";71 how the command to the rich man to sell all that he has and give to the poor is qualified by the condition, "if thou wouldst be perfect".72 The primitive Gospel is being whittled down before our eyes. As in Mark, the odium of the crucifixion is shifted in the First Gospel from Pilate to the Jews, who are made to shoulder the responsibility by the terrible cry: "His blood be on us and on our children!"73

The story of the virgin birth is a later insertion in the Gospel, perhaps made in Egypt, where such stories were popular. This is suggested by the story of the flight into Egypt in Matthew ii. The opening genealogy in i, which traces the descent of Jesus from David through Joseph, is pointless unless he was the son of Joseph. Some old manuscripts provide in i, 16, a natural conclusion to the genealogy by saying that he was Joseph's son; but most have been doctored to conform to the birth-story. The evangelist never refers to the virgin birth again, and follows Mark in making Jesus say that his disciples are his real mother and brothers. Evidently the First Gospel originally had no birth-story and, like Mark, held Jesus to have become Son of God by the descent of the Spirit at his baptism.

12. Luke Within a short time of the compilation of our First Gospel a far greater artist wrote the Third Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles. Their traditional ascription to Luke, the companion of Paul, has this in its favour, that Luke was not celebrated enough for much to be gained by fathering on him a work which he had not written. It is not impossible that, having known Paul in his youth, he wrote the Gospel and Acts as an old man forty or fifty years later. The Epistle to the Colossians (which, though not by Paul, embodies early information) calls Luke a physician. He was therefore representative of the middle-class Greeks who rallied to Paul and continued his work after his death. But Luke's authorship of the Gospel and Acts is attested by no one earlier than Irenaeus in the late second century, and even if a fact, is no guarantee of his reliability. Paul himself had disclaimed all interest in the Jesus preached by his Galilean rivals. His disciples doubtless shared his detachment until the exigencies of propaganda forced Gospel-making upon them.

The work of Luke must be later than the death of Domitian. His invariable representation of the Roman authorities as friendly (or at least benevolently neutral) to Christianity would have been too unconvincing under the Flavian emperors, but would be plausible under Nerva or in the early years of Trajan. We do not know where he wrote. Certainly not in Palestine, of which he has little knowledge, nor in Syria; for if so, he would show some knowledge of the First Gospel, or the First Gospel (if later) would show some knowledge of Luke, whereas neither seems to know anything of the other. Probably Luke wrote at Rome. The distance between Rome and Syria would explain the mutual ignorance of these two evangelists. Luke in his preface refers to "many" contemporary Gospel-writers, and in claiming accuracy and order for his own work censures theirs by implication.74

Like the compiler of Matthew, Luke dovetails Jewish and Pauline sources in order to produce a Gospel suitable for use in churches containing (as did that of Rome) both Pauline and Petrine elements. The opening birth-stories of John the Baptist and Jesus contrast sharply in style with the elegant Greek of the preface, and seem to be taken from a Jewish-Christian folk-poem. Luke preserves intact its frankly revolutionary language. Jesus is to recover "the throne of his father David" and to "reign over the house of Jacob for ever"; princes are to be "put down from their thrones", and those of "low degree" to be "exalted"; the hungry are to be "filled with good things", and the rich "sent empty away".75

This source knew nothing of the virgin birth. Luke i, 34-35, is a palpable interpolation, as is evident from the inept question ("How shall this be, seeing that I know not a man?") put into the mouth of Mary -- a girl about to be married -- in order to introduce the theme. Any doubt on the matter is removed when we find that in chapter ii Joseph and Mary are five times called the parents of Jesus, and that the virgin birth is never alluded to again. The naivety of the folk-poem is shown by the device of bringing the parents to Bethlehem on account of a census ordered by Augustus. Luke, who knew something of the Roman Empire, cannot really have supposed that a census necessitated everyone travelling from his home to the home of his ancestors a thousand years before! But the story was in his source and too popular to be omitted.

Luke inserts early in his Gospel a genealogy (different from that in Matthew) tracing the descent of Jesus through Joseph. This is one more proof that the virgin birth was not originally in the Gospel. The genealogy has been feebly doctored by interpolating the words, "as was supposed", in iii, 23. As in Matthew, the whole genealogy is pointless unless Luke believed Jesus to be really the son of Joseph.

From this point on Luke bases his narrative mainly on Mark, and his "sayings of Jesus" mainly on the primitive Jewish-Christian Gospel, but edits and embroiders his sources, sometimes to heighten the miraculous element in the story, sometimes to enforce the Pauline point of the rejection of the Jews and the acceptance of the Gentiles. Thus he antedates Mark's story of the rejection of Jesus at Nazareth, and dramatizes it by putting a provocatively anti-Jewish sermon into the mouth of Jesus and adding an attempt on his life and a miraculous escape. Luke's purpose is to stress the rejection of Jesus by the Jews at the very outset. He duplicates Mark's story of trie healing mission of the twelve by adding an account of a mission of seventy other disciples, peculiar to himself. This symbolizes the evangelization of the pagan world, seventy being in Jewish tradition the number of the nations, as twelve was the number of the tribes of Israel. After figuring in Luke's Gospel, the seventy disciples disappear without trace. Until the fourth or fifth century no one even pretended to know their names.

Luke preserves intact the blessings pronounced in the primitive Gospel on the poor and hungry, and does not suppress them like Mark or water them down like our First Gospel. But he qualifies them by stressing the spiritual and other-worldly nature of the promised blessing. Where Matthew speaks of the heavenly Father giving "good things to them that ask him", Luke speaks of the gift of the "Holy Spirit".76 In Luke Jesus rebukes a man who asks him to arbitrate between him and his brother over the division of their patrimony. Where Matthew has the revolutionary passage,

"Think not that I cameLuke turns a call to arms into a mournful prophecy:

To send peace on the earth:

I came not to send peace, but a sword!

For I came to set a man at variance with his father,""Think you that I am comeFollowing Paul, Luke repudiates the material millennium by making Jesus say: "The Kingdom of God is within you," or "in the midst of you."78 The Greek is ambiguous; but however we translate it, the point is that the kingdom is not a coming event, but is already present in the Christian community under the Roman Empire. Luke preserves the summons to the rich man to sell all that he has and give to the poor, but almost immediately neutralizes it by making Jesus promise salvation to a rich tax-collector, Zacchaeus, who gives away half. Every occasion is taken to exalt Pauline Christianity as against any sort of Judaism. The stories of the busy Martha and the contemplative Mary, of the prodigal son, of the ten lepers -- all peculiar to Luke -- ram home the moral that fulfilment of the law is nothing and acceptance of Christ everything. As in the First and Second Gospels, the onus of the crucifixion is transferred from the Romans to the Jews. Clearly Luke writes for a church where Paulinists are in control.

To give peace on the earth?

I tell you, No; but rather division . . .

They shall be divided, father against son,

And son against father."77Yet he is no uncompromising Paulinist. His aim is not to write a party pamphlet, but to cement the union of Pauline and Petrine Christians in one church by giving an account of Christian origins which shall please everybody. That is why, though no revolutionary, he preserves so many revolutionary sayings, merely balancing them by skilfully interpolated matter of his own. His Jesus is no mystery-god like Paul's, but a "man approved of God" and appointed by him "Lord and Christ".79 Luke underlines his humanity at every step. He depicts him as sprung from an obscure branch of the Davidic line, as a child growing "in wisdom and stature and in favour with God and man",80 as Son of God through the descent of the Spirit at his baptism, but not as himself God. Luke, and Luke alone, is responsible for such romantic embellishments as the scene with the sinful woman in the house of the Pharisee, the penitent bandit on the cross, and the walk to Emmaus. As if to put the divine claims of Jesus as low as possible, the centurion at the crucifixion, who in Mark and Matthew is made to say, "Truly this man was Son of God," in Luke only says, "Certainly this man was righteous."81 It is enough for Luke that a Roman officer should testify to the injustice of the crucifixion and therefore, by implication, to the injustice of later persecutions. Finally Luke breaks with Paul and conciliates his simple readers by giving the risen Jesus a body of "flesh and bones" that can walk, talk and eat.82 Luke has contributed more than any other single writer to the Christmas and Easter myths of popular Christianity.

Luke's second volume, the Acts of the Apostles, continues the work of reconciliation between Pauline and Jewish Christianity. To humour his Jewish-Christian readers Luke confines the name of apostle to the twelve. Later on he unobtrusively cancels the restriction by extending the title to Paul and Barnabas; but they remain loyal subordinates of the older apostles. All differences between Paul and the Palestinian apostles are suppressed. Peter leads the way in preaching the gospel to Gentiles and setting aside the Jewish law; Paul preaches nothing that Peter has not already preached, and is personally as strict a Jew as he. The speeches which Luke (after the manner of ancient writers) puts into the mouth of Peter and Paul proclaim in almost identical language that Jewish prophecies have been fulfilled in the death and resurrection of Jesus, and that salvation is open to all who repent and are baptized in his name. No one would gather from the Acts that there had ever been the rivalries and anathemas, charges and counter-charges which re-echo through Corinthians, Galatians and the Apocalypse.

Luke preserves the tradition of the community of goods in the primitive Palestinian church -- a tradition which, in view of the close connection of primitive Christianity with the Essenes, is doubtless founded on fact. But he qualifies it by making the pooling of property optional. Peter tells the delinquent Ananias that he need not have sold his land or handed over the price, and strikes him dead not for retaining the money, but for lying about it. As in the story of Zacchaeus, the amount of property surrendered is left to the owner's discretion. The rich after all are not "sent empty away"!

On one point Luke is uncompromising. He has no quarrel with the Roman Empire and will not allow that the Church has any. Roman officials are uniformly depicted as benevolently neutral, if not friendly to Christianity. Pilate tries to save Jesus (going even to the improbable length of finding "no fault" in one who claims to be king of the Jews) and yields at last only to the outcry of the Jewish mob.83 Cornelius and Sergius Paulus are converted to Christianity. Gallio refuses to hear the case of the Jews against Paul. Felix listens to Paul in fear. Festus sees nothing wrong with him but madness due to much learning. The centurion Julius treats him kindly, though a prisoner. Some of the details may be historical: the cumulative effect is to rouse suspicion. The only Gentile hostility to Christianity in the Acts is stirred up by unbelieving Jews, or comes from interested parties like the men who exploit the possessed girl at Philippi or who live on the cult of Artemis at Ephesus. In short the enemies of Christianity, according to Luke, are either Jews or racketeers. The Acts end with Paul waiting his trial at Rome and preaching unforbidden to all comers.

The inaccuracies, inventions and suppressions which abound in the Gospel and the Acts destroy Luke's credit as a historian. He remains one of the world's great romancers.

13. Trajan and the Christians Under Nerva, Trajan and their successors the Roman Empire entered on the reformist phase which so often immediately precedes the final breakdown of imperialism. The policy of government in the interests of the owning classes of the whole Empire was continued and developed; and concessions were made to the disinherited so far as this was necessary to provide for the defence of the Empire and to stave off complete social collapse. Attempts were made to arrest the depopulation of Italy by agrarian legislation, by better communications, by public provision for the maintenance and schooling of the children of poor freemen, and so forth. Such palliatives in no way affected the class structure of the Empire. Hence, in spite of the lull in persecution after the death of Domitian, official toleration of Christianity, in so far as it presented any sort of challenge to that class structure, was not to be expected. Not until the teeth of revolutionary Messianism were drawn could Christ and Caesar be at peace. That they were not completely drawn in the second century is proved by the popularity of apocalyptic writers and by the amount of revolutionary material which the Synoptic evangelists -- neutralize it how they might -- admitted to their Gospels. Christianity therefore remained under suspicion.

This was revealingly illustrated in in, when Trajan, in the course of a general tightening up of provincial administration, sent the tried and trusted Pliny to govern Pontus and Bithynia. Since the death of Domitian the Christians of those provinces had conducted an intensive propaganda which, by the time Pliny arrived, had led to a widespread desertion of pagan temples and to a slump in the sale of sacrificial animals. By Trajan's order Pliny issued an edict dissolving associations (collegia) of every kind. Not even a fire brigade was to be allowed in case it should turn into a political club! A veritable witch-hunt ensued. Anonymous informers sent Pliny long lists of alleged Christians in all walks of life. Some of these, when arrested, turned out never to have been Christians at all and proved it by invoking the gods, burning incense to the emperor's statue and reviling the name of Christ. Others had been Christians, but had lapsed long since and proved it in the same way. Others confessed Christianity and were executed or, if Roman citizens, were sent to Rome for trial.

Ex-Christians gave Pliny an account of the cult they had abandoned.

"They meet on a stated day before daybreak and sing in turns a hymn to Christ, as to a god. They bind themselves by a solemn oath, not to any wicked end, but never to commit fraud, theft or adultery, or to break their word or to deny a trust when called on to deliver it up. Then it is their custom to separate, and then to meet again and eat together a harmless meal."84Suspecting that there is more to it than this, Pliny puts to the torture two female slaves (deaconesses in the church) but discovers nothing. The worst he can prove against them is the "perverse and extravagant superstition" of worshipping an executed rebel. Feeling that this enquiry into un-Roman activities is getting beyond him, he writes to Trajan for guidance. Trajan is obviously in two minds about it. He plumes himself on being a progressive and dislikes a witch-hunt. He tells Pliny not to look for Christians, and to ignore anonymous denunciations as "foreign to the spirit of our age". But if Christians are charged, they must be punished unless they clear themselves by worshipping the gods of Rome.85

This correspondence proves two things. The fact that Pliny can find no evidence of sedition shows that in Pontus and Bithynia at any rate the Pauline leadership had successfully restrained the rank and file from revolutionary action. But the fact that Pliny and Trajan nevertheless consider Christianity punishable with death shows that the odour of revolution still clung to it. Paul's attempt to inoculate the masses against revolutionary Messianism by spreading the cult of a purely mystical Christ had ended in a fusion between the Pauline mystery god and a crucified Jewish rebel whose worship not even the most liberal of emperors could allow to flaunt itself in the light of day.