H. J. Eysenck, Sense and Nonsense in Psychology (1957).

There are two contradictory points of view widely held among many people nowadays, and frequently even held by the same people at different times. Some believe that a person's political opinions are the results of objective experiences, of thought, and of definite decision; they are consciously arrived at after a thorough weighing of the evidence and are modifiable by logical argument and factual proof. The opposite view is that political opinions are the reflections of personality, determined largely by irrational motives of one kind or another, not amenable to logical argument or factual disproof, and altogether an expression of personality rather than a reaction to external reality. Many people feel that the former of these two views adequately characterizes the voting behaviour of themselves and their friends; the second type of motivation may be recognized more easily in those voting for the opposite camp.

Chapter 7

POLITICS AND PERSONALITYAmong those who usually, or at least at certain times, hold the view that personality factors are at least partly responsible for political views and social attitudes, there is again a good deal of agreement on what are the basic traits which are responsible for a person's choice of political party. Their political opponents, so they declare, are driven to their opinions by their lack of intelligence, their emotional instability, and their chronic selfishness, which makes them put class before country; conversely, those who think like themselves are characterized by high intelligence, emotional stability of an outstanding quality, and an imperturbable integrity which makes them scorn prizes held out by rival politicians.

Unlikely as such beliefs might appear, they have given rise to a considerable amount of experimental work in the social sciences, particularly in the United States. Quite a large number of researches have been conducted on the hypothesis that Socialists, who form a relatively small minority group in America, are lacking in emotional stability. The results, by and large, have failed to disclose any such differences between Socialists and members of the Democratic and Republican parties respectively. Other studies, involving the measurement of intelligence, have shown a slight degree of superiority of the more radical as opposed to the more conservativej this superiority, however, seems to have been restricted to University students in the 1930's and does not seem to apply to less highly selected samples at different times during this century. Altogether, it may be said that attempts, until quite recently, to link up personality and political beliefs have been restricted to the contrast between conservative and radical opinions and have nearly always resulted in failure. It is interesting to inquire into the reasons for this failure and to show how, by more determined application of the scientific method, success can be achieved in this field also.

We may begin by taking account of two contradictory types of statement which are frequently made and which, being partial in their application, impede rather than further the scientific study of social and psychological issues. The first point of view to be mentioned here is one frequently held by the more old-fashioned social scientists in this country, by many politicians, and, implicitly at least, by many groups of people who have only a tangential relation to social science, such as historians, economists, and sociologists. This point of view might best be expressed in the following form. Empirical investigations in the social sciences have a much lower and much less important status than have philosophical arguments, scholarly reviews of opinions held by well-known writers (preferably dead), and argumentations about possible causes of historical events. Factual studies are looked upon with distaste because they force a reconsideration of cherished values and beliefs, and because they do not usually fall in line with patterns of thought formed many years ago.

This vague distaste for empirical work, which is quite common in this country, has recently found a somewhat more virulent expression in the United States. The 83rd Congress established in 1953 a special committee to investigate Tax Exempt Foundations, under the chairmanship of Mr Rees. This committee collected evidence on the support given by the Foundations to Social Science Research, and made a special point of the criticism of empirical investigations. The views expressed are so illogical and unclear that it is difficult to know precisely what is implied. The type of insinuation made is exemplified by statements like the following: 'It may not have occurred to (foundation) trustees that the power to produce data in volume might stimulate others to use it in an undisciplined fashion without first checking it against principles discovered through the deductive process.' If this statement means anything -- a point which is, of course, debatable -- it means that facts should not be discovered if they disagree with principles discovered through the deductive process, i.e. if they disagree with the a priori opinions of a person, or group of persons, in charge of an inquiry, or conducting a Congressional Committee investigation. This type of argument is, of course, quite common in Russia (and in Hitlerite Germany), where either no factual investigations in the social sciences are carried out at all, or where the investigator is told beforehand in no uncertain terms what kind of results are expected from him. It is, however, a little disturbing to find such views expressed in what is, effectively, an agency of the Congress of a democratic nation.

It is easy to see why such distrust of factual empirical research in the Social Sciences should arise among politicians and others who have an axe to grind. Their success and their very existence are predicated upon their ability to persuade a large enough number of the population that the particular beliefs they hold, and the panaceas they advocate, are in some way advantageous to the community as a whole. They are opposed by other politicians asserting precisely the opposite, and, with the usual swing of the pendulum, both sides in due course have their intoxicating draught of power given to them by the electorate. They are well used to this particular type of game and, by and large, have no ill feelings towards their opponents.

The matter immediately becomes charged with emotion, however, when the social scientist appears and says, 'Here we have two opposite sets of hypotheses; let us not waste time in talking about which is nearer the truth, but let us go and carry out an experiment to see which hypothesis is, in fact, nearer the truth.' Such a proposal is almost invariably considered by the politician as a threat to his particular position in society. He has no means himself of carrying out an investigation of this kind and, quite usually, he will even be incapable of understanding the results if they are presented to him. He knows how to deal with a fellow politician and with arguments he has heard a thousand times before, but the party line will give him little support against the upstart social scientist who takes these theories seriously and actually wants to find out whether they work or not!

While it is thus easy to see why politicians should be somewhat chary of employing the empirical approach, it is difficult to see why the man in the street should have any objections against it. As the President of the Social Science Research Council has put it: 'To approach a problem empirically is to say: "Let's have a look at the record." To apply the empirical method is to try to get at the facts. Where feasible, counting and measuring and testing are undertaken. There is nothing necessarily technical about empirical methods and there is no simple distinctive empirical method as such. Congressional investigating committees normally follow an empirical approach. To imply something immoral about using an empirical method of inquiry is like implying that it is evil to use syntax.' The alternative to an empirical study is speculation, aimless debate, and unsupported theorizing. As John Locke, the famous British philosopher, often called the father of empiricism, said to a friend who mentioned to him some rationalistic speculations by a Continental philosopher, 'You and I have had enough of this kind of fiddling'.

In spite of the Rees Committee, then, we may conclude that the social sciences, if they are to be anything at all except idle speculation and arid, dry-as-dust scholasticism, must have an empirical foundation; in other words, they must be securely founded on ascertained facts. But is this enough? Many social scientists seem to feel that the answer here is 'Yes', and it is this second belief which I think requires even more careful analysis and refutation than the first. It is less obviously nonsensical but, none the less, it is probably equally fatal to the development of a true science of personality and social life. The reason for this belief is a very simple one. Science is defined as systematic knowledge, not just as knowledge, and while the empirical content is certainly an absolutely essential part of it, the system, or organization, of this empirical content is at least equally important. What the scientist is looking for is not a large number of disconnected facts; it is rules or laws which bind together large groups of facts and make it possible, once a law is known, to deduce these facts from it. Results have been published in many different countries of thousands of different Gallup Polls on all sorts of issues. These results provide a considerable amount of empirical content, but they do not make Gallup Polling into a science. Only if it were possible to find some general rule or law running through all these results, and making it possible to deduce the individual results from the general law, would all this work make a genuine contribution to science.

A simple example may illustrate this point. Hundreds of thousands of stars have been discovered in the sky. All of these are approximately circular in appearance, and there is little doubt, therefore, that they are, in fact, spherical, or very nearly so. Let us suppose that a new star has been discovered. If we were asked to give an opinion as to its shape, what would our answer be? Presumably, very few people would fail to predict that this newly discovered star would also be spherical, and the most common reason given for this prediction would be that in the past all stars have been observed to be spherical, and that the new one, presumably, would not be an exception. This kind of argument does not lack empirical content (after all, a large number of stars have actually been observed in the past), but nevertheless it is not a scientific argument. The scientist, when asked his opinion, would make the same prediction as the man-in-the-street, but he would make it on quite different grounds. He would argue that, according to Newtonian laws of physics, any large body made up of physical substances would, in the course of time, assume a spherical shape. He would be able to make this prediction even if no other stars had ever been seen before, by a simple deduction from certain known laws. It is the existence of such laws and the possibility of going deductively from the law to the individual fact, and inductively from a set of facts to a given law, that characterizes science as opposed to the mere collection of isolated and unrelated data.

Empirical work is at the foundation of science, but empirical research is not enough. It must be guided by and lead to theories of general significance and laws of deductive power. Only under these conditions can we talk about a field of study as being a science. As T. H. Huxley once put this point in his pithy way, 'Those who refuse to go beyond fact rarely get as far as fact; and anyone who has studied the history of science knows that almost every great step therein has been made by the anticipation of nature; that is, by the invention of a hypothesis which, though verifiable, often had little foundation to start with; and not infrequently, in spite of a long career of usefulness, turned out to be wholly erroneous in the long run.'

If this is so, and scientists, logicians, and philosophers of science are in full agreement that these are some of the essential characteristics of scientific endeavour, can we consider psychology and the social sciences as being truly scientific? As a matter of fact, have they reached this stage, or are they still in a pre-scientific stage of gathering isolated facts and other unconsidered trifles? The answer, I think, must be that some parts of psychology have already passed into the scientific stage, others are still in a pre-scientific stage. To those who would doubt the first part of this statement I would like to offer the remainder of this chapter as an example of the possibility of achieving deduction from general laws and empirical verification of such deductions, which we have just seen to constitute the essence of science.

The first thing that strikes us when we look at the field of social attitudes, political behaviour, party strife, and voting is that none of it appears to be innate in any sense, but that all of it is due to some form of learning. However much it may appear at certain moments as if the old jingle were true, and 'Every boy and every girl that's born into this world alive is either a little radical or else a little conservative', yet in our heart of hearts we know that this is not so. Just imagine the reactions of an Eskimo to an election campaign largely waged in terms of the nationalization of the steel industry, or that of a Zulu, whose opinions are sought on the relative importance of Federal as opposed to State rights! We learn our politics as we learn our language, and if we wish to know anything about political attitudes, then we should be able to turn to the laws of learning in our efforts for further clarification.

When we do this, we see that there appear to be two laws rather than one. These two laws have been recognized for a very long time indeed, although it is only in quite recent years that they have been stated in a sufficiently clear form to be amenable to experimentation. We might call these laws the law of hedonism and the law of association. The law of association simply states that we learn that A is followed by B because in the past A and B have always, or often, been associated with each other. The law of hedonism, on the other hand, maintains that we learn things because they have some effect on our well-being. Simple association is not enough; it must be followed by some kind of reward or punishment.

These two views may be summarized in terms of two experiments. To characterize the associationist view we may have recourse to Pavlov's dogs, which we discussed in a previous chapter. The simple association, repeated over a number of times, of bell and meat causes the dog to learn that the bell is followed by the meat, and to respond with salivation to the sound of the bell alone. In the Skinner box, on the other hand, also mentioned in a previous chapter, the rat produces a pellet of food by accidentally striking a bar in its cage which is connected with a food reservoir; the relief from hunger produced by this action causes the rat to learn this particular movement whenever food is desired. These two different types of modification of the animals' nervous system as a result of experience may be called conditioning and learning respectively.

We must now inquire into the consequences in the political field which may be deduced from our knowledge of these two different processes. Let us begin by noting certain facts about the society in which we grew up, facts which every youngster learns in the course of his early life. The first fact we must know is that people differ with respect to their social status. By status we mean such things as the amount of money a man earns, the kind of education he has had, or which he can afford for his children, the kind of house he lives in, and the part of the town in which he lives, his accent, the kind of people he mixes with, and so on and so forth. At the one extreme we have the millionaire, who lives in a huge house, in an exclusive quarter of the town, employs several maids and butlers to look after him, runs several cars, sends his children to Eton and Oxford, sports an old school tie, and speaks with what everybody recognizes as a 'superior' type of accent. At the other end we have a down-and-out, dozing on a bench in the Embankment, with no one to look after him, shabby clothes, little food, and an accent almost unintelligible to anyone not familiar with the particular portion of the country he comes from. Between these extremes there are all sorts of gradations, but, by and large, there is little difficulty in fitting people along a continuum from the one to the other.

For practical purposes it is often useful to group people into a number of status groups. There are many such classifications. Typical of them is that used by the Gallup Poll. Their top, or Av+ group, is characterized as follows: 'Well- to-do men (or their wives) working in the higher professions, e.g. wealthier chartered accountants, lawyers, clergymen, doctors, professors, or in higher ranks of business, e.g. owners, directors, senior members of large businesses. Almost invariably they will have a telephone, car, and some domestic help.

'Av: Middle and upper middle class: Professional workers not in the top category. Salaried clerical workers such as bank clerks: qualified teachers: owners and managers of large shops: supervisory grades in factories who are not manual workers: farmers, unless their farm is very big when they will be Av+. Many will have a telephone, a car, or employ a "char".

'Av : Lower middle and working class: by far the biggest group. Manual workers, shop assistants, cinema attendants, clerks, agents.

'Group D: Very poor: people without regular jobs or unskilled labourers or living solely on Old Age Pension. Housing will be poor. They can only afford necessities.'

Many psychological features are correlated with this division of people into different status groups. The average intelligence quotient of the Av+ men (but not necessarily their wives) would be 140-150; that of the Av group would be in the neighbourhood of 120; that of the Av group would be slightly below 100; and that of Group D would be around 90. I have discussed such relationships in some detail in Uses and Abuses of Psychology and will not do so again here. Suffice it to stress that the concept of status is not purely defined in terms of positions, but is also related to psychological concepts.

In addition to status, which is an objective fact which can easily be ascertained with regard to any particular person, we have another concept which is much more subjective in character, but which is also of considerable importance in our analysis. That is the concept of social class. Whatever their objective status may be, people in the democratic countries tend to think of society as being grouped into various classes, and they tend to consider themselves as belonging to one or other of them. This knowledge and this belief can be seen to develop quite early in the lives of our children; by the time they leave school they are as well acquainted with the concepts of class structure as are their parents. While the concept of class is subjectively dependent on each individual's private opinions and beliefs, it does, in fact, have a strong factual relation to social status. The Av+ group tends to think of itself as upper and upper-middle class; the Av group tends to think of itself as middle class; while the Av- group, and more particularly the very poor, tend to think of themselves as working class. The relationship between social status and social class is shown below in Table 3. Figures were obtained on a national sample of about 9,000 people by the British Institute of Public Opinion. It will be seen that social class (as estimated in each case by the person interviewed for himself) and social status (as estimated by the interviewer after talking to the people concerned) do show considerable agreement. In actual fact this Table underestimates the amount of agreement which exists between the two concepts because the interviewer's estimate of a person's status is known to be far from completely reliable. When correction is made for that, agreement becomes considerably higher than is shown in the Table.

TABLE 3

Relationship Between Social Status and Social Class

Class Status Upper and

upper middleMiddle Lower

middleWorking Don't

know(per cent) Av + 57 36 4 3 Av 16 58 13 10 3 Av- 2 20 20 55 3 Very poor 7 8 76 11 We thus start our analysis with two widely known and universally accepted facts, namely, that people differ with respect to status and that they are aware of these status differences, and as a consequence of them regard themselves as belonging to certain social classes. We may go on by noting that certain political issues may arise which will further the ends of people belonging to one social class and be opposed to the interests of people belonging to another social class. Indeed, it would be difficult to find many issues which do not in some way fall into this category. This well-known truth is often put in the form of an analogy by referring to a national cake; however it is sliced, some people will receive more than others and the interests of one group will almost infallibly be opposed to the interests of another group. Under these conditions, it seems almost inevitable that political groups should arise to represent these respective interests, and, indeed, as is well known, groups of parties have arisen in all the democratic countries which represent this difference of interests. By long-established custom those parties representing the interests of the high status groups are called conservative parties, or parties of the right, while those parties representing the interests of the low status groups are called radical parties, or parties of the left.

This bifurcation represents an inevitable consequence of the law of learning and can be directly deduced from it. A radical government, acting so as to further the interests of the low-status groups, will thereby benefit members of the low status groups, and thus reward them for having voted for this particular party. Conversely, a conservative government acting so as to further the interests of the high-status groups will thereby benefit members of the high status groups, and thus reward them for having voted for this particular party. A rat in a box which receives food when it presses a red lever and an electric shock when it presses a blue lever will very soon press the one and avoid the other. Similarly, voters who receive benefits from one government and have their status position lowered by another government will soon learn to vote in accordance with their interests. There is nothing very mysterious or difficult about this deduction, and, indeed, the general principle is fairly universally accepted. Table 4 shows the relationship between social status and political attitude in Great Britain; again, it must be remembered that the relationship would be even closer if estimates of social status were more reliable. Even as the figures stand, however, there can be little doubt that in a representative sample of the population there is a close relationship between voting and social status. There is a similar close relationship between social class and voting behaviour. Of those who consider themselves to be upper- or upper middle-class, 79 per cent vote Conservative, whereas only 20 per cent who consider themselves to be working class do so. Only 5 per cent of the self-styled upper class group vote Labour, whereas over 90 per cent of those who consider themselves working- or lower middle-class do so.

TABLE 4 Relationships Between Social Status and Political Attitude Status Conservative Labour Liberal Other Don't Know Total Number (per cent) Av + 77 8 11 3 447 Av 63 16 12 1 10 1,855 Av 32 47 9 1 11 4,988 Very Poor 20 52 9 1 18 1,621 Total Number 3,411 3,545 894 60 1,001 8,911 It might be asked why the relationship is not perfect. If our generalization is true and if the law is as stated, then surely all working-class people should vote Labour, and all middle-class people Conservative. This is not so for a number of reasons. In the first place, in our teaching a rat to press one bar and avoid another, a large number of repetitions are required of bar pressing behaviour. Conversely, the number of elections in which a person takes part is relatively limited; few people voting this year have voted in more than four or five previous elections. It follows that the amount of reinforcement received is relatively small, and consequently a good deal of random behaviour is to be expected.

Furthermore, in the case of the rat experiment, the reward is inevitable and follows immediately. In the case of political actions, the reward is not infallible and may not follow immediately. At a given time the working class may be better off under a Labour government than they would be under a Conservative government at the same time, yet because of world conditions outside the control of any British government, their absolute well-being might be less than that which they enjoyed under a previous Conservative government. Under those conditions, the reinforcement picture is rather confused, and one would not expect a perfect class alignment with voting behaviour.

Another point that arises is that voting behaviour may be used to express feelings and emotions irrelevant to the issues concerned. Thus, the son of a harsh and inconsiderate Conservative father may vote Labour, not because he feels any affinity for the Socialist faith, but simply because he wants to annoy his father. Conversely, the son of an equally harsh Socialist father may vote Conservative for the same reason. Causes of this type are not in any sense systematic and will tend in the long run to cancel out. They do, however, serve to make the correspondence between social class and status, on the one hand, and voting behaviour on the other, to be in less than perfect agreement.

It will now be clear why we would not expect, and, indeed, do not find any kind of correlation between personality and political behaviour as far as the right-left, or conservative-radical continuum is concerned. It may be possible that very stupid people are slower to learn where their real interests lie, thus perhaps voting against the party which would, in fact, benefit them most. It is also possible that some neurotic and emotionally unstable individuals may, for obscure and irrational reasons, be opposed to the party which best embodies their interests. There may be many other individual features which in any given case make a particular person react in ways which are contrary to the generalization which we have established. However, these exceptions are not of a systematic kind; the stupid working-class person who might vote against his interests would be balanced by the stupid middle-class person voting against his interests, and thus there would be no correlation between intelligence and tendency to vote for one party rather than another. Thus, while these individual tendencies make the law less than perfectly applicable, they do not produce any kind of systematic tendencies.

One word should perhaps be said about the position in the United States at the moment. It is often said there that the country is relatively free from conceptions of social class, and that the great political parties are not divided as European parties are on any class basis. Nothing could be further from the truth. Numerous studies have shown that Americans consider themselves members of the working-class or the middle-class to pretty much the same extent as do people in England, France, or Germany. It has also been found that the political tie-up with class and status is quite strong in the United States also. By and large, low-status groups and people who consider themselves working-class tend to vote for the Democrats, while higher-status groups and people who consider themselves middle-class tend to vote for the Republicans. The relationship between class and status, on the one hand, and voting behaviour on the other, is not quite as strong as it is in European countries, but it has been increasing in strength over the years, and there is every reason to believe that in a few years the party structure and party alignment in the United States will in every way duplicate that observed over here.

We have now dealt in some detail with the consequences to be expected from the hedonistic law of learning; we must now consider the consequences to be derived through the associationist law of conditioning. In doing this we must have recourse to the argument already presented in an earlier chapter. There it will be remembered it was shown that the differences in a person's innate capacity to form conditioned reflexes easily and quickly were responsible for marked individual differences in temperament, particularly along the extraversion-introversion continuum. We also saw that the amount of socialization which a given person succeeded in requiring was, to a great extent, determined by his 'conditionability'. Thus, a person in whom conditioned reflexes were formed easily and quickly will tend to become 'over-socialized' in comparison with the average, but a person who forms conditioned reflexes slowly and with difficulty will tend to become 'under-socialized' in comparison with the average.

In the fields of social behaviour and social attitudes the two fields in which socialization should most clearly show itself are the fields of sexual and aggressive behaviour. It is here that we have the most obvious conflict between very strong and powerful individual wishes and desires, and equally strong and powerful social prohibitions and restrictions. Much the greater part of the process of socialization may be said to consist in the erection of barriers to the immediate satisfaction of aggressive and sexual impulses. These barriers are absolutely essential if society is to survive and in some form they exist even in the most primitive type of society. Yet, however essential they may be to society, they are irksome and annoying to the individual, who finds himself thwarted in the expression of what, to him, are perfectly natural wishes and desires. Thus, here is a potential area of great conflict, and it is here, if anywhere, that we would expect the most marked contrast between the extravert and the introvert; the easily conditioned and the poorly conditioned. How would this conflict show itself in the field of social attitudes and political behaviour?

Our expectation follows directly from what has been said so far. We would expect to find a continuum ranging from the introverted type of attitude to the extraverted type of attitude, from the over-socialized to the under-socialized. On the one side we would expect a strong insistence on barriers of one kind or another to the free expression of sexual and aggressive impulses. These barriers might be of a religious nature or an ethical nature, but what would be common to all the beliefs and attitudes on this side would be a desire to restrict the open expression of socially unacceptable behaviour. On the other side of the continuum, we would expect to find the opposite, that is to say, a relatively open demand for a relaxation of prohibitions, an overt desire for the direct expression of sexual and aggressive urges, and the denigration of religious and ethical standards felt to stand in the way of such open manifestations. On the one hand then, we should find a tender-minded regard for conventions and rules protecting society from the more biological drives of human nature; on the other hand, we should find a tough-minded desire to over-ride these conventions. and seek direct expression of these animal instincts.

Thus, our hypothesis would lead us to predict the existence, in addition to our conservative-radical continuum, of a tough-minded versus tender-minded continuum, quite unrelated to that of radicalism and conservatism, and therefore cutting clean across the more widely known and popular political schism. Before we turn to the evidence to see whether, in fact, this prediction is borne out, let us first of all look briefly at the structure of political groupings and parties in this country. As Mr Disraeli said: 'Party is organized opinion', and a study of attitude organization as embodied in the major parties will therefore be relevant to our problem.

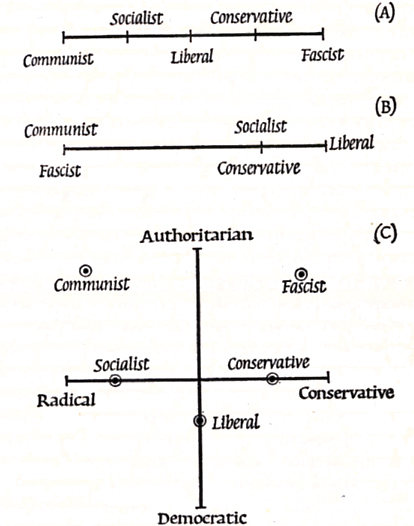

In considering the mutual relations between the parties, we find that two apparently contradictory theories are quite widely held. The main groups in this country, Conservatives, Socialists, Liberals, Communists, and Fascists, are often thought to be arranged along a continuum from left to right, so that the Communists are supposed to lie at the extreme left, the Socialists a little nearer the centre, the Liberals in the middle, the Conservatives to the right, and Fascists at the extreme right. This theory is represented graphically in Figure 6a.

Figure 6: Diagrammatic representation of three hypotheses regarding the structure of attitudes as mirrored in the relative positions of different political parties On the other hand, many people find this arrangement quite unconvincing. They argue that Communists and Fascists have something in common which sets them off against the democratic parties, and that to put them at opposite ends of a continuum is manifestly absurd. Consequently, it is argued, we should really have a different kind of continuum, at the one end of which we would put Communists and Fascists, at the other end the democratic parties. Sometimes the argument is taken a little further, and it is said that the democratic parties also can be separated out on this continuum, with the Liberals being at the opposite extreme to the Communists and Fascists, and the Socialists and Conservatives a little less strongly opposed to the tenets of these two authoritarian parties. This hypothesis is shown diagrammatically in Figure 6b.

There is no doubt that most people would find some degree of truth in both these hypotheses, contradictory to each other as they may appear. This contradiction can easily be resolved, however, if we decide that what is needed is not one dimension or continuum but two, placed at right angles to each other. One of these two continua, the radical-conservative one, would sort out the parties in line from the Communist at the left to the Fascist at the right; the other continuum, which we may perhaps call the authoritarian- democratic continuum, would lie at right angles to the first and sort the parties out with the Communists and Fascists at the authoritarian end and the Liberals at the democratic end. This solution is shown in Figure 6c. It is presented at the moment purely as a hypothesis and not as a factual statement; we will see later that the evidence in favour of a hypothesis of this type is rather strong and that Figure 6c does seem to represent reality to a considerable approximation.

We may go one step further and ask ourselves whether we cannot identify this group of political parties with the organization of attitudes which we have deduced from the principles of learning and conditioning. The radical-conservative continuum appears in both hypotheses and we may readily accept the likelihood of our dealing with identical concepts here. Can we go further and identify the authoritarian-democratic continuum with our hypothetical tender-minded versus tough-minded continuum? On a priori grounds, and judging from general knowledge and observation, there appears to be some justification for this. The high degree of aggressiveness of the non-democratic parties in this country is well known, as is also the extremely loose sexual morality characterizing so many of the adherents of the two extremist groups. (What is true of Communists in Europe, Great Britain, and the United States does not necessarily apply to the U.S.S.R. or other countries in which the Communists have gained power.) However, common-sense judgements of this kind have no scientific value, and while they may make a particular solution appear reasonable, they cannot serve as proof. Consequently, we must next turn to the task of providing such proof, if, indeed, it can be found.

In looking for proof in favour of our hypothesis we must first of all state a little more precisely what it is that we are asserting. We are asserting that attitudes and opinions on social issues are not independent of each other, but are organized and structured; in other words, they tend to appear in clusters. Furthermore, we are suggesting that there are two main sets of clusters which together account for the major part of the interrelations observed between different attitudes. One of these clusters we have called the radical- conservative one; the other cluster we have called the tough-minded versus tender-minded one. What kind of evidence can we adduce, first to show that attitudes are in fact related to each other, and secondly to show that these relations give rise to the two sets of clusters we have specified?

The answer to the first part of this question is a relatively easy one, and it depends essentially on the statistical method of implication. Let us take two logically independent attitude statements. For instance, 'Jews are cowards' and 'The Jews have too much power and influence in this country'. Logically there is no relationship between these two statements. A person may be a coward without having much power and influence in the country, and, conversely, a person may have a good deal of power and influence without being a coward. Therefore, logically, there is no indication that a person endorsing one statement should also endorse the other. We can, however, posit that there is a continuum of anti- Semitism such that some people will tend to endorse all anti-Semitic statements while others will endorse none of them. If that were true, then we would find that, in fact, people would tend either to endorse both statements or to endorse neither; relatively few people would be found to endorse one but not the other. Let us suppose that we have interviewed a thousand people and that, as indicated below, 450 have endorsed both statements, 350 have endorsed neither statement, 100 have endorsed the statement that Jews are cowards, but not that they have too much power and influence in this country, while another 100 have endorsed the statement that Jews have too much power and influence, but not the one that they are cowards (these figures are quite fictitious and put in merely for the purpose of illustration) .

The Jews have too much power and influence YES NO The Jews are cowards YES 450 100 NO 100 350 It will be seen from this table that there is, indeed, a factual implication from one statement to another. The person who believes that Jews are cowards is four and a half times as likely to believe that Jews have too much power and influence in this country as a person who does not believe that Jews are cowards. We can measure the strength of implication existing in a table of this kind and express it in the form of a single figure. This figure is usually referred to as a coefficient of correlation, and varies from zero, when there is no implication at all, to 1.00, when there is perfect agreement. If the number of people in each of the four cells of our table had been exactly 250 there would have been no implication, and the correlation would have been zero. If the number of cases in the cells agreeing with both statements, had been 500, and 500 disagreeing with both statements, then the implication would have been complete and the correlation would have been 1.00. Knowing the person's opinion on one issue would have determined completely his opinion on the other issue.

In actual fact correlations between different attitudes usually range from about 0.2 at the lower end, to about 0.7 or 0.8 at the higher end. Thus, there is a definite amount of implication in the field of social attitudes, but these implications represent tendencies, not certainties.

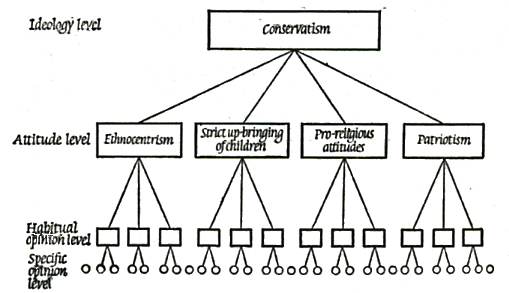

When we study, by statistical methods, the actual implications found in large samples of the population we find that they are organized in a kind of hierarchical system. At the bottom of the hierarchy we find a million and one casual expressions of attitude or opinion which we make in the course of our lives. Some of these are characteristic of our long-range views, others are purely ephemeral and may just be the outcome of a temporary annoyance. Thus, the driver who has his new car scratched by an incompetent lady who drives in a rather haphazard manner may be moved to call out some deprecatory remark concerning woman drivers, without, in his more sober moments, necessarily endorsing the anti-feminist position implied. It is only when opinion statements are made on more than one occasion that we reach a relative stability of opinion which makes it worthwhile to measure and record the expression. Thus, if a person on several occasions gives it as his opinion that children should be seen and not heard, then we may regard this as a genuine expression of opinion.

Such opinions themselves are intercorrelated; we have seen an example in the case of the two views that 'Jews are cowards' and that 'Jews have too much power and influence in this country'. Relationships such as these, which involve a large number of opinions regarding one central issue (attitude towards the Jews in this case) give rise to a somewhat higher-order concept than that of opinion, namely the concept of attitude. Attitudes themselves, however, are not unrelated, and when we analyse their relationships we come to a higher-order construct yet, namely, that of an ideology, such as, for instance, the ideology of conservatism.

A hierarchical system such as this is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Diagrammatic representation of the structure of attitudes

In viewing this figure, it should be remembered that the relationships implied therein are not in any sense arbitrary, or based on a priori considerations on the part of the investigator. The Figure simply represents in a diagrammatic form actual relationships observed between attitudes and opinions held by representative samples of the population. The implication from one opinion or attitude to another is a factual one; its measurement is based on the expressions of points of view made by thousands of people who are selected at random from the general population. This is an important point to remember. What the psychologist contributes is a theory and a method of analysing and organizing the data. The actual content of this scheme, however, is contributed by the people whose opinions and attitudes he is analysing. His hypothesis may call for a high correlation between two opinions, but whether such a high correlation does or does not obtain is a factual question which only empirical research can answer.

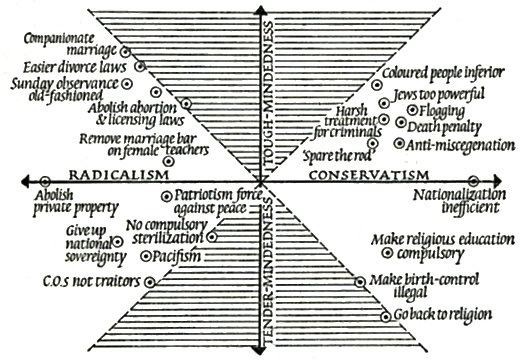

What, then, is the verdict of empirical research of this kind when applied to the hypotheses we are considering at the moment? The result of carrying out detailed analyses of this kind on samples of several thousand men and women, both working class and middle class of all degrees of education, of all ages, and voting for all the different political parties in the country, is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Relationship of different social attitudes to each other and to the two great principles of organization as determined empirically

We can see there the organization of opinions and attitudes, as objectively determined by the calculus of implication, and it will be seen that the outcome strongly supports our general theory. There are, indeed, two main opposed sets of ideologies corresponding to the radicalism and conservatism and the tough-minded and tender-minded one respectively. Conservative beliefs apparently include the view that nationalization is inefficient; that religious education should be made compulsory; that coloured people are inferior; that birth control should be made illegal; that the death penalty should be retained; and so forth. Radicals, on the other hand, believe that private property should be abolished; that Sunday observance is old-fashioned; that we should give up our national sovereignty in the interests of peace; and so forth. That these items do, in fact, represent conservative and radical opinion can be shown by a very simple calculation. The percentage of endorsements for each item was calculated separately for Conservative and Labour party voters who were equated for social class, education, age, sex, and other important variables. Then the difference in the percentage of endorsements was calculated for each item and it was found that the views mentioned above, as well as the others given in the Figure, did in fact show very marked differences in endorsement between Conservative party voters and Labour party voters. There seems to be no doubt, therefore, that we are here dealing with a genuine radical-conservative continuum.

How about the tough-minded-tender-minded continuum? It will be seen that this bears out very strongly our prediction. On the tough-minded side we have openly aggressive and sexual attitudes. The aggressive ones favour flogging, the death penalty, harsh treatment for criminals; corporal punishment for children; and so forth. The openly sexual attitudes are those in favour of companionate or trial marriage; easier divorce laws: the abolition of abortion laws, thus making abortion easily available to everyone; and so on. On the other hand, attitudes characterizing the tender-minded end of the continuum emphasize ethical and religious restraints and pacifism; the giving-up of national sovereignty; going back to religion; and making religious education compulsory; the making illegal of birth control and the abolition of flogging and the death penalty -- these are characteristic of tender-minded views. There appears to be, therefore, considerable evidence in this analysis of attitudes that our deduction is verified.

We have not, however, shown so far that our analysis of the relationships between political parties is as predicted in Figure 6c, and to this task we must now turn. If our hypothesis is correct, then we would expect Communists to be tough-minded radicals; Fascists to be tough-minded conservatives ; Liberals to be tender-minded and intermediate with respect to the radicalism-conservatism continuum; Socialists and Conservatives should be intermediate with respect to tender-mindedness between the authoritarian parties and the Liberals, and to the left and right, respectively, on the radicalism-conservative continuum. Proof of this prediction was sought in the following way. Questionnaires were made up of items which best characterized the conservative-radical continuum and the tough-minded- tender-minded continuum; these two questionnaires we shall call the R inventory and the T inventory respectively. These inventories may be considered as reasonably reliable and valid measures of our two continua. They were tried out and refined in a number of studies, and finally applied to large groups of people who were members of, or had voted for, the various party groups with whom we are dealing. Their scores on these two inventories were then determined and plotted. When this was done it was found that our prediction of the relative positions of these various groups were borne out in very considerable detail. The only discrepancy occurred with respect to the Fascist group, which was indeed tough-minded and Conservative, but slightly less conservative than voters for the Conservative party. In all other details, the prediction was precisely fulfilled, and we may therefore conclude that our hypothesis possesses a considerable degree of predictive value.

The reader may be interested in assessing his own and other people's position on these two continua. For this purpose I have given below a 60-item inventory which can be scored for both the R and the T continuum. The reader may like to fill this in first before looking at the key. The instructions preceding the inventory are those normally given with it. The key to this, as well as the method of scoring and the average scores for various representative samples, are given at the end of this chapter.

SOCIAL ATTITUDE INVENTORY Below are given sixty statements which represent widely-held opinions on various social questions, selected from speeches, books, newspapers, and other sources. They were chosen in such a way that most people are likely to agree with some, and to disagree with others.

After each statement, you are requested to record your personal opinion regarding it. You should use the following system of marking:

+ + if you strongly agree with the statement

+ if you agree on the whole

0 if you can't decide for or against, or if you think the question is worded in such a way that you can't give an answer

- if you disagree on the whole

-- if you strongly disagreePlease answer frankly. Remember this is not a test; there are no 'right' or 'wrong' answers. The answer required is your own personal opinion. Be sure not to omit any questions. The questionnaire is anonymous, so please do not sign your name.

Do not consult any other person while you are giving your answers.

Opinion Statements Your Opinion 1. The nation exists for the benefit of the individuals composing it, not the individuals for the benefit of the nation. 2. Coloured people are innately inferior to white people. 3. War is inherent in human nature. 4. Ultimately, private property should be abolished and complete Socialism introduced. 5. Persons with serious hereditary defects and diseases should be compulsorily sterilized. 6. In the interests of peace, we must give up part of our national sovereignty. 7. Production and trade should be free from government interference. 8. Divorce laws should be altered to make divorce easier. 9. The so-called underdog deserves little sympathy or help from successful people. 10. Crimes of violence should be punished by flogging. 11. The nationalization of the great industries is likely to lead to inefficiency, bureaucracy, and stagnation. 12. Men and women have the right to find out whether they are sexually suited before marriage (e.g. by trial marriage). 13. 'My country right or wrong' is a saying which expresses a fundamentally desirable attitude. 14. The average man can live a good enough life without religion. 15. It would be a mistake to have coloured people as foremen over whites. 16. People should realize that their greatest obligation is to their family. 17. There is no survival of any kind after death. 18. The death penalty is barbaric, and should be abolished. 19. There may be a few exceptions, but in general, Jews are pretty much alike. 20. The dropping of the first atom bomb on a Japanese city, killing thousands of innocent women and children, was morally wrong and incompatible with our kind of civilization. 21. Birth control, except when recommended by a doctor, should be made illegal. 22. People suffering from incurable diseases should have the choice of being put painlessly to death. 23. Sunday-observance is old-fashioned, and should cease to govern our behaviour. 24. Capitalism is immoral because it exploits the worker by failing to give him full value for his productive labour. 25. We should believe without question all that we are taught by the Church. 26. A person should be free to take his own life, if he wishes to do so, without any interference from society. 27. Free love between men and women should be encouraged as a means towards mental and physical health. 28. Compulsory military training in peace-time is essential for the survival of this country. 29. Sex crimes such as rape and attacks on children, deserve more than mere imprisonment; such criminals ought to be flogged or worse. 30. A white lie is often a good thing. 31. The idea of God is an invention of the human mind. 32. It is wrong that men should be permitted greater sexual freedom than women by society. 33. The Church should attempt to increase its influence on the life of the nation. 34. Conscientious objectors are traitors to their country, and should be treated accordingly. 35. The laws against abortion should be abolished. 36. Most religious people are hypocrites. 37. Sex relations except in marriage are always wrong. 38. European refugees should be left to fend for themselves. 39. Only by going back to religion can civilization hope to survive. 40. It is wrong to punish a man if he helps another country because he prefers it to his own. 41. It is just as well that the struggle of life tends to weed out those who cannot stand the pace. 42. In taking part in any form of world organization, this country should make certain that none of its independence and power is lost. 43. Nowadays, more and more people are prying into matters which do not concern them. 44. All forms of discrimination against the coloured races, the Jews, etc., should be made illegal, and subject to heavy penalties. 45. It is right and proper that religious education in schools should be compulsory. 46. Jews are as valuable citizens as any other group. 47. Our treatment of criminals is too harsh; we should try to cure them, not punish them. 48. The Church is the main bulwark opposing the evil trends in modern society. 49. There is no harm in travelling occasionally without a ticket, if you can get away with it. 50. The Japanese are by nature a cruel people. 51. Life is so short that a man is justified in enjoying himself as much as he can. 52. An occupation by a foreign power is better than war. 53. Christ was divine, wholly or partly in a sense different from other men. 54. It would be best to keep coloured people in their own districts and schools, in order to prevent too much contact with whites. 55. Homosexuals are hardly better than criminals, and ought to be severely punished. 56. The universe was created by God. 57. Blood sports, like fox hunting for instance, are vicious and cruel, and should be forbidden. 58. The maintenance of internal order within the nation is more important than ensuring that there is complete freedom for all. 59. Every person should have complete faith in some supernatural power whose decisions he obeys without question. 60. The practical man is of more use to society than the thinker. There are one or two more points which should be discussed. The first of these relates to class differences in tough- mindedness. We have seen that from our hedonistic learning field we can predict that working-class groups should be predominantly radical in their sympathies, while middle-class groups should be predominantly conservative. Can we make any prediction about class differences from our associationist conditioning hypothesis? The answer appears to be in the affirmative. So far we have assumed in our deduction that people who condition easily and people who condition with difficulty are also submitted to a socialization process which is roughly equal in strength or superiority for all of them. This, however, is surely not true to the facts. We know that some children are submitted to a very strict process of socialization, others to a very lax one indeed. The outcome, undoubtedly, will be determined not only by the degree of conditionability of the child, but also of the amount of conditioning to which he is subjected. Given an equal degree of conditionability in a group of children, we would expect those to be most 'over-socialized' who have been subjected to a very strict socialization process and those to be 'under- socialized' who have been submitted to a very lax process of socialization.

Now, there is no reason to assume any differences between social classes with respect to conditionability, but there are very good reasons for assuming considerable differences between them with respect to the degree of socialization to which they are subjected. Particular attention has been drawn, for instance, by Kinsey in the United States to the different value laid on the repression of overt sexual urges by middle-class and working-class groups. He has shown that where, for middle-class groups, parents put very strict obstacles in the way of overt sexual satisfaction of their growing children, and inculcate a very high degree of' socialization' in them, working-class parents, on the whole, are much more lax and unconcerned. In many working-class groups, for instance, he found pre-marital intercourse viewed as not only inevitable, but as quite acceptable to the group.

Similarly, with respect to aggression, there is a considerable amount of evidence from a variety of sociological studies, carried out both in the United States and in Great Britain, to show a tendency for middle-class groups to impose a stricter standard upon their children than the working-class groups. The open expression of aggressiveness, which is frowned upon in the middle-class family, is often not only accepted but even praised in the working-class group.

There are, of course, many individual exceptions which will immediately occur to the reader. There are middle-class families where parents completely fail to impress social mores and customs upon their children, and where the open expression of anti-social tendencies is openly condoned, or at least not strongly discouraged. Conversely, in many working-class families, particularly where there are ambitions for the children to move in the direction of the higher-status groups, there is an extremely strong tendency to stress conventional values and inculcate respect for them in the children. However, in spite of numerous exceptions, available data leave little doubt that, on the average, there are differences between social classes and status groups which, by and large, allow one to generalize in the direction of stating that the socialization process is stronger and more complete in middle-class than in working-class groups.

If that is so, and if we have no reason to expect innate differences in conditionability between the two groups, then we would expect our middle-class groups to be more tender- minded than our working-class groups. This hypothesis has been put to the test by applying the T-inventory to groups of working-class and middle-class individuals, matched on a number of relevant variables. The outcome was exceedingly clear-cut. Middle-class Conservatives were more tender- minded than working-class Conservatives; middle-class Liberals were more tender-minded than working-class Liberals; middle-class Socialists were more tender-minded than working-class Socialists. Indeed, even middle-class Communists were found to be more tender-minded than working-class Communists! Not enough Fascists were available to carry out a comparable study with them, but for all the other groups considerable differences were found in the predicted direction, and we may therefore generalize and say that middle-class people, on the whole, tend to be more tender-minded, working-class people on the whole more tough-minded. There is, of course, considerable overlap, but of the existence of a noticeable average difference there can be no doubt.

Another question that may concern us is that of national differences. Most of the work mentioned has been carried out in Great Britain, and it does not necessarily follow that what is true of Great Britain is true of other countries. Fortunately, a number of studies are available to show that the organization of attitudes in France, Germany, Sweden, and the United States is very similar indeed to that found in this country. Similarly, the relationships of the R and T dimensions to political parties are similar to those observed here.

There are, however, certain differences which in themselves are very enlightening; thus, in Great Britain the major political parties are differentiated almost entirely in terms of the radicalism-conservatism continuum, and comparatively little with respect to tough-mindedness and tender- mindedness. Socialists and Conservatives are approximately equal with respect to their degree of tough-mindedness; the Liberals are a little more tender-minded, but the difference is not very large. It is only the minority groups, like Communists and Fascists, which show considerable deviation from the norm.

When we turn our attention to France, however, the position is very different. There it has been found that the T-dimension, very far from being negligible, is, on the contrary, even more important than the radicalism-conservatism dimension. Whereas in Great Britain the ratio of importance for these two factors is approximately 10 to 1 in favour of radicalism-conservatism, in so far as the major political parties are concerned, it is 4 to 3 in favour of tough-mindedness-tender-mindedness in France. (This might, indeed, have been expected in view of the well- known strength of the Communist and of various Fascist groups on the French political scene.)

This finding is very important to anyone who wishes to compare the political structure in England and France. In this country parties are divided from each other in terms of radicalism-conservatism; the division between tough- minded and tender-minded usually divides each of the major parties into sub-sections. In France, on the contrary, the major divisions are with respect to tough-mindedness- tender-mindedness, and the radical-conservative dichotomy is frequently found within each of the major parties. The position is not so clear in France as it is in this country because there the two principles, or dimensions, are of approximately equal strength. Nevertheless, a tendency is there, and it will be apparent now why it is so very difficult for British observers, used to our type of political organization, to understand the quite different pattern on the French political scene. If the reader, in studying French politics, will bear in mind these considerations, I think he will find his task considerably eased and his understanding grow correspondingly.

What about countries and nations outside the European circle of circumstance and background? We may expect the tough-minded-tender-minded dimension to remain in some form because it is grounded on relatively universal and permanent characteristics of human beings. We would not, however, expect to find the radical-conservative dimension to emerge in the same form as here unless social conditions have given rise to classes and status groups of a similar nature to those dominating the social scene in the European and North American countries. In a feudal society, for instance, you would not expect to find anything resembling our conservative-radical continuum to emerge.

Only one study has been carried out along these lines in a semi-feudal country. Among mid-Eastern Arabs it has been found that while the tough-minded-tender-minded dimension is still clearly expressed in the relationships observed between different attitudes there is nothing that corresponds to the radical-conservative continuum. It could be of the very greatest interest if studies of this kind could be carried out in countries like China, Russia, and so forth, but the practical difficulties and the financial outlay involved make it unlikely that in the near future our knowledge will grow by an inclusion of these countries in our circle of exploration.

It will have been noticed that nothing has so far been said of an implication in our theory which would link personality with tough-minded and tender-minded attitudes respectively. We have argued, on the one hand, that a person difficult to condition should develop tough-minded attitudes. In a previous chapter we have argued that a person difficult to condition should develop extraverted patterns of behaviour. Similarly, we have argued in this chapter that persons particularly easy to condition should develop tender- minded attitudes, and in a previous chapter we have argued that such a person should develop introverted behaviour patterns. It seems reasonable to expect, therefore, that a tough-minded person would tend to be extraverted, and a tender-minded person would tend to be introverted. This hypothesis has been put to the test several times, and results in each case have strongly supported this hypothesis. There appears to be a definite tendency for extraverted people to develop tough-minded attitudes, whereas introverted people show an equally definite tendency to develop tender- minded attitudes. With this finding our set of hypotheses has indeed come full circle, and we now see in detail the relationships obtaining between personality, social attitudes, and political action. Considering the many sources of error involved in the measurement and determination of personality and of social attitudes, the relationships found are remarkably close. Nevertheless it should be remembered that they are not perfect. We have found that Communists tend to be extraverted, tough-minded radicals, whereas Fascists tend to be extraverted, tough-minded conservatives. It should not be deduced from that that the converse also holds and that all extraverted, tough-minded radicals are Communists and all extraverted, tough-minded conservatives are Fascists. All policemen are over 6 feet tall, but not all men over 6 feet tall are policemen; the argument from the one to the other cannot be reversed. (I understand that regulations about the height of policemen, like most other things, has been subject to change and nowadays one can behold policemen who are only five feet nine inches tall. I have attempted to obtain empirical evidence on this point, but have been awed by the curious headgear worn by policemen which makes any measurement of their height extremely unreliable.)

Indeed, it would not even be true to say that all members of the Communist party, say, are in fact tough-minded radicals. People join a party for all sorts of reasons and it would be unreasonable to expect perfect conformity. To take an extreme case, an agent provocateur, or police spy, might join an extremist party in order to keep an eye on it; you would not expect him necessarily to share its views and attitudes. Again, we have found in several cases that a husband belonging to, say, the Communist party is made to persuade his wife to join also; she may join because she does not want to break up her marriage, but without in fact sharing the beliefs and aims of the party. There will always be a number of people in a party whose membership is based on considerations more or less tangential to the views held by the party and germane to its functioning. These people would not be expected to show identical attitudes with those held by the major set of party members.

Our systematic analysis is relatively complete so far, but we may still feel that a somewhat more detailed analysis of the personality of members of the Communist and Fascist parties might reveal more than is contained in the general statement that they tend to be extraverted. This suspicion is probably well-grounded, but unfortunately it is extremely difficult to obtain the co-operation of members of extremist groups for the purpose of studying their personality structure. Communists, on the whole, are rather more co-operative, but Fascists are extremely suspicious and distrustful, and refuse point-blank any requests for co-operation. In the circumstances, comparatively little has been done, but even the few isolated results which are available are of considerable interest.

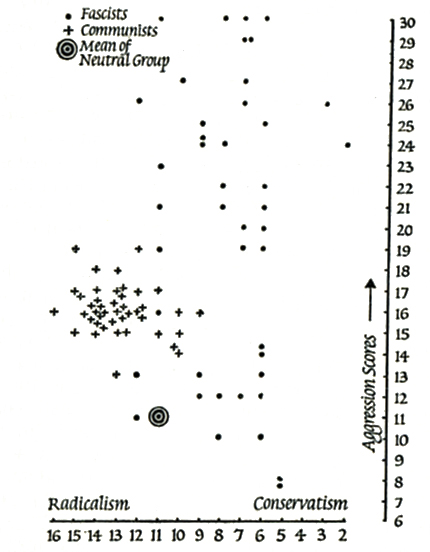

One such study carried further the hypothesis, outlined near the beginning of this chapter, that a special characteristic of Fascist and Communist groups would be their aggressiveness, i.e. their failure to become properly conditioned to the social prohibitions regarding the open expression of violence against other people. Forty-three Communists and forty-three Fascists were studied in this particular experiment, and their reactions compared with those of a group of eighty-six people equated with them from the points of view of age, class, and social status, but differing in that they held political views favouring one of the three democratic parties. In addition to being given the radicalism-conservatism questionnaire, these three groups were also tested by means of the Thematic Apperception Test, described in an earlier chapter. Special attention was paid in the analysis of the stories the subjects told to evidence of aggression of both an overt and a covert nature. Scoring along these lines is quite reliable when the scorers adhere to the definition of aggression adopted for this purpose, which was 'To hate, fight, or punish an offence. To criticize, blame, accuse, or ridicule maliciously. To injure or kill, or behave cruelly. To fight against legally constituted authorities; to pursue, catch or imprison a criminal or enemy.' Each person was given a score according to the number of times that clear evidence of aggression was found in his stories. The result of the analysis is shown in Figure 9,

Figure 9: Aggression scores of Fascists and Communists as compared with a neutral group

where scores on the radicalism-conservatism scale are shown on the abscissa, and aggression scores on the ordinate. It will be seen that each and every one of the Communists had aggression scores which were in excess of the mean of the neutral group, i.e. the group of people voting for the three democratic parties. The same, with very few exceptions, is true of the Fascists who took part in this experiment; only four of these have aggression scores slightly lower than the neutral group. All the others have aggression scores very much higher than the neutral group.

An inspection of the actual stories told by Fascists and Communists reveals them to be dripping with blood. This is particularly true of many of the stories told by the Fascists; the amount of aggressiveness found in these stories is quite beyond the range of what is found in normal people. It will be seen from the Figure that scores as high as thirty are not unusual among Fascists as compared with the mean for the normal group of about eleven. Communists, by contrast, are somewhat more aggressive than average, but not abnormally so; their mean is in the neighbourhood of sixteen. These data suggest certain differences between Communists and Fascists, but for want of more detailed investigations it is not possible to follow up this lead.

Other investigations of a similar nature have shown Fascists and Communists to be more dominant than members of the democratic parties, to show a certain amount of rigidity, and some intolerance of ambiguity. Suggestive as these findings are, it must be obvious that much more thorough experimental inquiries are needed before we can claim to have gained but a superficial understanding of the personality dynamics which cause a person to become a member of the Communist or Fascist party.

The reader, comfortably seated in his arm-chair in front of the fire, and glancing through the pages describing these results, will almost certainly feel, as does the writer, that they do little more than whet the appetite, and he may wonder why more has not been done in this field. One of the main reasons is the great difficulties which lie in the path of the investigator. Let us take but one example. To have administered the Thematic Apperception Test and a few questionnaires to forty-three Fascists and forty-three Communists may not sound a very considerable task. Yet the student who did this work had to spend approximately a year in simply gaining access to meetings held by these parties, obtaining the confidence of a few members in each, and thus preparing the ground for the heart-breakingly difficult task of individually persuading forty-three members of each group to undergo the testing programme. All this had to be done without revealing the purpose of the experiment, without losing the co-operation of a member once he had been approached (this would have upset the sampling procedure), and without allowing the members of one party to suspect that she was in any way friendly with members of the other party. Almost every Saturday evening, come rain or shine, snowstorm, blizzard, or hail, this intrepid young lady attended open-air political meetings; most of her evenings were spent arguing, debating, and reading party literature so as to be able to talk the accepted jargon. Inevitably, personal complications arose which had to be resolved. All through the time that this work was being carried on there was a risk of personal danger if any suspicions had been allowed to arise with respect to her exact role. Few students are willing, or capable, of carrying out scientific research of a high standard under these conditions, and the majority rest content with the less interesting, but more easily obtainable types of data.

In spite of all these obvious and very great difficulties, it might be possible to induce some of the more adventurous students to take up research of this kind if society showed some interest in the results so laboriously acquired, but unfortunately experimental social science is not welcomed very much in academic quarters, where the quiet somnolence of the reading-room and the dead and forgotten writings of past nonentities are considered much more soothing than the fresh air of empirical investigation, and the intoxicating flood of factual data. Until this general attitude changes, it is idle to expect any great access of knowledge in these complex and difficult fields.

Figure 10: Empirically determined positions of Communists, Socialists, Liberals, Conservatives, and Fascists on two main dimensions

KEY TO SOCIAL ATTITUDE INVENTORY The scoring key for the two scales is given after each of the items. There are sixteen items for the measurement of R and thirty-two items for the measurement of T; some items are used for measuring both dimensions. Some items in the scale are 'filler' items and are not scored at all. As regards scoring, the R scale is always scored in the radical direction. For items marked R+ in the key, agreement (+ or ++) is scored 1, and any other response 0. For items marked R-, disagreement (- or --) is scored 1, and any other responses 0.

The T scale is always scored in the tender-minded direction. For items marked T+, agreement (+ or ++) is scored 1, and any other response 0. For items marked T-, disagreement (- or--) is scored 1 and any other response 0. The range of scores in the T scale is from 0 to 32; the range of scores in the R scale is from 0 to 16.

In comparing these scores with those of members of various political groups, the reader will find Figure 10 useful.

In this are shown the actual mean scores of Communists, Fascists, Socialists, Liberals, and Conservatives on the R and T scales. By entering his own score in this table, the reader will be able to see how he stands with respect to the major political organizations in this country.

Below are given sixty statements which represent widely-held opinions on various social questions, selected from speeches, books, newspapers, and other sources. They were chosen in such a way that most people are likely to agree with some, and to disagree with others.

After each statement, you are requested to record your personal opinion regarding it. You should use the following system of marking:

+ + if you strongly agree with the statement

+ if you agree on the whole

0 if you can't decide for or against, or if you think the question is worded in such a way that you can't give an answer

- if you disagree on the whole

-- if you strongly disagreePlease answer frankly. Remember this is not a test; there are no 'right' or 'wrong' answers. The answer required is your own personal opinion. Be sure not to omit any questions. The questionnaire is anonymous, so please do not sign your name.

Do not consult any other person while you are giving your answers.