Roy M. Robbins, Our Landed Heritage: The Public Domain, 1776-1936 (1942).

Part I

The Settler Breaks the WayCHAPTER I

FOUNDING THE SYSTEM

Among the grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence was the complaint that the King of Great Britain endeavored to "prevent the population of these States" by "obstructing the laws for naturalization of foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their emigrations hither, and raising the conditions of new appropriations of lands."1 For over one hundred and fifty years the colonies had enjoyed the privilege of moulding their own land systems, but the Proclamation of 1763, and subsequent Orders in Council leading up to the Quebec Act of 1774, served notice to Americans that frontier policy was no longer a matter for colonial initiative but had become an imperial problem of first order. This interference with the free movement of colonists into the country west of the Appalachians was resented by southern and New England colonies alike,2 and constituted one of the major causes of the American Revolution.

The policy of the British government was not without its critics even in England. Adam Smith, the chief protagonist of a new school of economics, pointed out in his The Wealth of Nations, first published in 1776, that "plenty of good land, and liberty to manage their own affairs their own way, seem to be the two great causes of the prosperity of all new colonies."3 Looking at the colonies of the different European nations, he observed that British institutions were more conducive to the improvement and cultivation of land than were those of other countries. In British colonies engrossment of uncultivated lands was not very extensive; colonists suffered less from taxation and were allowed a more comprehensive market. The result was a strong demand for labor with correspondingly liberal wages. Hence when the government of George III began to impede the free flow of labor to the colonies, or from the colonies into the trans-Appalachian West, it was interfering with one of the vital privileges of empire. England was just beginning to feel the first impulses of the Industrial Revolution; philosophers everywhere were predicting a new world order. Adam Smith was diligently striving to work out a new philosophy which would synthesize the rising industrialism in England and the political and economic democracy of America. But he spoke too late. The statesmen of the old order, whose minds had been conditioned by mercantilism and the classic literature of Merrie England, were unable to adjust their policies to meet the new situation. Soon after the Declaration of Independence the problem of disposing of the vacant lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, claimed by seven of the states, became the subject of considerable controversy.4 If the Revolution was successful and the larger states were allowed to persist in their claims, then the six smaller states with definite boundaries would find themselves hemmed in along the coastline with no future to the west. Was not the sovereignty west of the mountains, the small states asked, being assured more by the artillery of Knox and by the rifles of Morgan than by the parchments issued by some mouldering potentate with little conception of new world geography? Maryland, ringleader of the small states, boldly contended that this unsettled domain to the westward, if wrested by the "common blood and treasure of the thirteen states" should be their common property. The lands should be under congressional control, to be "parcelled out" into "free, convenient, and independent governments, in such manner and at such times" as Congress should determine.5 It had been imperial policy since 1763, Maryland's leaders recalled, to limit original charter grants. Besides, the seven claimant states could never reconcile differences based on conflicting claims and overlapping boundaries. The State of Maryland thereupon refused to accede to the Articles of Confederation, blocking the establishment of any common government until some concessions should be made by the larger states.

Finally, in 1780, to alleviate the dissatisfaction among the smaller states, New York tendered her western lands to Congress without reservation.6 In the same year Congress passed a resolution "earnestly" recommending that other states having like possessions do the same, and declaring that "the unappropriated lands which should" be ceded or relinquished to the United States by any particular state "should be disposed of for the common benefit of the United States, and be settled and formed into distinct republican states which should become members of the union and have the rights of sovereignty and freedom and independence like the other states -- the lands to be granted or settled at such terms and under such regulations as should afterwards be agreed upon by the United States in Congress assembled."7

Not until 1784, however, did Virginia magnanimously relinquish her claims to the country northwest of the Ohio, reserving certain areas.8 Meanwhile, Maryland had agreed to ratify the Articles of Confederation. These cessions made possible the first legal union of the thirteen states, and conveyed to the government of these united states the title to a body of land known as the public domain. Between 1784 and 1802 the remaining five states also ceded their western lands.9 The public domain thus had its origin in a curious compound of the states-rights feeling which characterized the so-called "critical period" in American history and the growing spirit of nationalism which was to mark the years to come.

The government of the United States thereupon assumed toward the immense bodies of western lands the position of a trustee of sociery, holding not only the right of eminent domain but also the right of individual ownership. Realizing that this relation should continue no longer than was absolutely necessary, it became the anxious desire of the Confederation government to transfer the title into private hands.

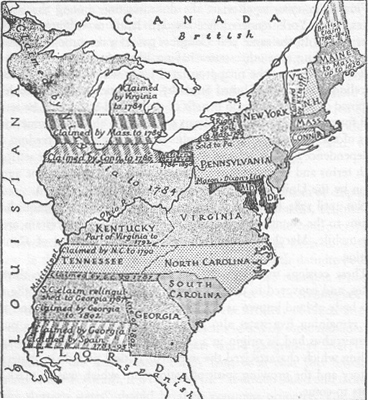

The Land Claims of the Thirteen States.

From Nathaniel W. Stephenson, A History of the American People.

By permission of Charles Scribner's Sons.

By 1784, financiers, ex-soldiers -- in whom General George Washington was vitally interested -- and many other persons were already calling upon Congress to adopt some sort of policy for the alienation of western lands. This was the one national problem upon which most of the states agreed that Congress could act. Several workable plans were presented by individual citizens, but the congressional committee overlooked these for the most part, and proceeded to formulate a policy based upon land systems already in operation among the various states.

Colonial experience attested to the fact that the nature of society was to a very great extent determined by land policy. New England had been settled compactly under a well-regulated township system. A group of individuals desiring to break away from the more established community was required to incorporate, whereupon it received from the colonial legislature a rectangular tract of land definitely bounded and surveyed. This "was an admirable method for assimilating the wilderness to a definite civilization, but too deliberate, restrained, and social for eighteenth century pioneers of the Kentucky breed."10

In the proprietary colonies land had been disposed of for revenue purposes, the proprietor exacting an annual quitrent from the grantee.11 This aristocratic system provoked the wrath of the colonists, especially in Pennsylvania, and was one of the main forces leading to the establishment of a democratic government in that state. With the Revolution, most of the new state constitutions abolished quitrents and other aristocratic incidents. The type of survey constituted another distinguishing feature of land policy in the proprietary colonies. In most of the middle and southern colonies land was located indiscriminately. This practice tended to scatter the population over a wide area; it favored squatters at the expense of permanent settlers; and it encouraged irregular surveys, as well as carelessness in the recording of titles.12 Both the New England and the southern systems had merits. The former "afforded a security of title which facilitated an orderly settlement of new lands," while the latter "encouraged initiative and resourcefulness."13 One made for the evolution of a community type of life, while the other tended to develop the plantation type of civilization.14

Congress devoted a year of study to the western land problem. Thomas Jefferson was chairman of the committee and the first draft of an ordinance, dated 1784, is in his own handwriting. But Jefferson's appointment as ambassador to France removed this important southern and democratic influence from the drafting committee, and the Ordinance of May 20, 1785, reflects a predominant New England influence.

In line with the earlier abolition of feudal incidents, the ordinance adopted allodial tenure, that is, land was to pass in fee simple from the government to the first purchaser. After clearing the Indian title and surveying the land the government was to sell it at auction to the highest bidder. Townships were to be surveyed six miles square and alternate ones subdivided into lots one mile square, each lot consisting of 640 acres to be known as a section. No land was to be sold until the first seven ranges of townships were marked off. A minimum price was fixed at $1 per acre to be paid in specie, loan-office certificates, or certificates of the liquidated debt, including interest. The purchaser was to pay surveying expenses of $36 per township. Congress reserved sections 8, 11, 26, and 29 in each township, and one-third of all precious metals later discovered therein. In addition the sixteenth section of each township was set aside for the purpose of providing common schools.15

| Township = 36 sections | |||||

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 30 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 25 |

| 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 |

Despite its many defects, the Ordinance of 1785 "proved to be one of the wisest and most influential of all the acts of the Revolutionary period."16 It inaugurated a system of land surveys which, perfected by practice and experience, has been adopted by nearly every civilized country in the world. No act of the Confederation government evinced a more genuine national spirit. This ordinance together with the better known Ordinance of 1787 "guaranteed the American colonist against exploitation" by the national government or by any of the original thirteen states, and thus formed the basis for the American colonial system.17

The new federal constitution of 1787 did not interfere with the democratic principles of empire established in these two ordinances. A liberal western colonization policy was among the first subjects discussed in the Constitutional Convention,18 and to the southern delegates must go the credit for preserving the policy of free and unhampered development of the West. The Constitution when finally completed gave Congress power "to make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory of the United States." The new federal government, under this general provision, accepted with but little discussion the legislation of the Confederation Congress. Probably none of the Fathers of the Constitution then imagined that this liberal settlement policy would lead to rapid settlement of the West and that this newer region would ultimately hold the balance of power in national affairs.

Well might this national land system be considered democratic in comparison with the aristocratic systems of the Old World, but as compared with the land systems of the original thirteen states, it was strongly conservative. Lands in western New York were selling at 20 cents to $1 an acre, with credit advanced to the purchaser.19 Massachusetts had reduced her Maine lands to 50 cents an acre to check possible migration to the West. Pennsylvania's rates were low at its state office; and Virginia's rich lands in Kentucky were selling at give-away prices. So also were the Tennessee lands owned by the Carolinas and Georgia. Consequently for some years the eastern states were able to outbid the national government for settlers."20

Regardless of the comparatively democratic character of the Ordinance of 1785, the American settler found little within its provisions that was attractive. The policy appealed more to speculators and men of money than to hardy yeomen who were usually unable to compete with the former at the auction. The pioneer generally hated the speculator who offered him smaller parcels of land at advanced prices. He therefore had to risk the uncertainties of squatter settlement on government land or else to seek his future on the state lands of the East.

The fact is that much of the history of the national land system centers around the struggle between these two forces of squatterism and speculation, between the poor man and the man of wealth. Ever since early colonial days the danger of frontier revolt had menaced established society. The opening of vacant lands to the westward always stimulated a frontier spirit -- a peculiar democratic levelling influence, likely to be arrogant, daring, dangerous, and even uncontrollable. The frontiersmen wanted free access to the soil, but the forces of established order, on the other hand, contended that free land would destroy the economic and political values upon which government was founded.

All the colonial governments in America had very early adopted ironclad policies to control these peculiar levelling influences from the backwoods. So long as the movements of population were on a small scale, and for the most part onto vacant lands within the eastern states, the dominant forces of established order could control this frontier spirit. But once settlement spread beyond the reach of the colonial governments, and the western population of squatters and trespassers stood ready to defy the law of the land, danger became imminent. By 1785 the state governments of North Carolina, Virginia, and Pennsylvania with their far-flung frontiers, had found it advisable to compromise with these revolutionary forces by granting the right of preemption.21 Briefly, the government pardoned the squatter for his illegal settlement and in addition confirmed his title on condition that he buy at a much-reduced price. Preemption was at best an expedient by which established law and order were made to conform to the lawless and uncontrollable spirit of the American frontier.22 But it was the means by which thousands of acres of land were to be settled by a sturdy and enterprising population. The next half century was to see constant friction between the squatter and the speculator, each seeking indulgences from the national government on the pretext that he was doing more than the other in developing the nation's resources. The land policy established under the Ordinance of 1785 benefited the speculator at the expense of the settler. In truth, the ink was scarcely dry on the statute book when the Congress of the Confederation, in dire need of money, departed from the provisions of the ordinance and sold extensive tracts of public land in Ohio to eastern speculators at prices far below the minimum price established in the ordinance.23 Under the direction of the Reverend Manasseh Cutler, a group of Revolutionary veterans of New England organized the Ohio Company of Associates and signed a contract on October 27, 1787, for a million and a half acres of land on the Ohio and the Muskingum rivers, to be known as the Ohio Purchase. The price if paid in depreciated Continental certificates was to be 8 to 9 cents per acre.24 At about the same time certain members of Congress organized the Scioto Company and dealt out to themselves at similar prices, five million acres along the Ohio River east of the Scioto. A third contract was made in 1788 with Judge John Cleves Symmes, a member of Congress from New Jersey, for the tract between the Great Miami and the Little Miami rivers, at the same bargain rates.

These three grants, together with Connecticut's Western Reserve in northeastern Ohio, the Virginia Military Reserve in southern Ohio, and Clark's Reserve in southern Indiana, marked the beginning of a period in which the national government attempted to settle the western country through the agency of land speculators. It was an unfortunate experience. The most that can be said in favor of this policy is that it led to the establishment of Marietta, Cincinnati, Manchester, Chilli-cothe, Gallipolis, Cleveland, and other towns, and hence the conquest of the Ohio Wilderness was begun. From the standpoint of land policy, settlement by large land companies was a failure. The Scioto Company collapsed soon after the arrival of a coterie of poor French immigrants who had been induced by rather questionable tactics to settle at Gallipolis. The Ohio Company met only its first payment. Symmes made his first payments then proceeded to sell the land which did not legally belong to him.25 When the federal government began to function in 1789 the land question immediately assumed extraordinary importance. Representatives from the frontier regions agitated for a general preemption law and some went so far as to demand free land.26 A representative from western Pennsylvania voiced the typical western argument for a democratic policy when he inquired, "What will these men think who have placed themselves on a vacant spot, anxiously waiting its disposition by the government," when they "find their preemption right engrossed by the purchase of a million acres? . . . They will do one of two things: either move into Spanish territory, or . . . move on United States territory, and take possession without leave. . . . They will not pay you money. Will you then raise a force to drive them off? . . . They are willing to pay an equitable price for those lands; and, if they may be indulged with a preemption to the purchase, no men will be better friends to the government. . . . The emigrants who reach the western country will not stop till they find a place where they can securely seat themselves."27

That settlers would seek the lands of Spain in Florida and Louisiana was a real threat, for at this time the Spanish policy was very lenient.28 The Spanish "hold out temptations," complained Governor St. Clair of the Northwest Territory, "that will succeed with many who have little other governing Principle beside the Desire for Wealth -- a thousand acres of land, free of Purchase and Taxes -- ten Dollars per hundred for Tobacco, and six Dollars for Pork or Beef delivered at New Orleans are offered to all who will remove into Florida, and produce those Articles."29 St. Clair even went so far as to recommend "laying open a part of the Western Territory for those who want land and cannot pay for it immediately." These lands "might be set at a moderate rate and an Office opened, where any person might locate them in small Quantities, and where, upon the payment of the purchase Money, which should run upon Interest, they should receive Patents." As for the sale of large tracts of land to speculators, he commented further: "It seems certain that the Sale of the Country in large Districts, if it ever was an eligible manner of disposing of it, is now over. . . . The Expectation that the Domestic Debt might be paid off . . . by selling that Country in large Portions, was never very well founded," and is now "very much lessened." Building up the population in the Northwest, with adequate military protection, he felt, would do much to check British influence and guarantee control of this region to the United States.30

Congress listened attentively to the arguments for a more liberal land policy until the condition of the treasury was pointed out, when prospects for a revolutionary change in policy at once disappeared. Congress did, however, put an end to the practice of selling extensive tracts of land to proprietors.

While no liberal policy was forthcoming, President Washington's administration did much to put the western domain in order. In 1790 the President warned the American public by proclamation against the questionable speculative activities of the Yazoo Land Company of the Southwest. In 1789-90 Governor St. Clair established many counties in the Northwest Territory. The year 1790 also saw the creation of the Territory Southwest of the Ohio. A treaty was signed at New York City with the powerful Creek Indian Confederation of the Southwest, and in the course of the next four years the federal government moved against the Indians of the Northwest. The Treaty of Greenville, concluded in 1795, relieved the Northwest of the Indian menace for the next few years and opened up to settlement much of the present state of Ohio. The treaty with Spain in 1795, which assured free navigation of the Mississippi River and settled the Florida boundary, encouraged migration into the new Southwest. This forceful, paternalistic and protective policy on the part of the federal government did more than anything else to lessen the dissatisfaction in the western country. The admission of Vermont, Kentucky, and Tennessee into the union attested to the faith of the administration in the western country.31

It was not for lack of interest on the part of President Washington that no important land legislation was passed until the end of his administration. With eastern lands cheap and plentiful, with Indians menacing settlers throughout the West, with Easterners disinclined to run the hazards of western pioneering, and eastern land interests jealous and reluctant to open up western lands, there was little need for a change in land policy.

Alexander Hamilton's report on federal land policy, which was included in his important analysis of the country's resources and economic prospects, published in 1790-91, did not attract much immediate attention. Men of Hamilton's way of thinking placed considerable emphasis upon the financial benefits to the government which might be derived from the proceeds of the sales of public lands.32 And these men exercised power out of all proportion to their numbers in the early days when the federal government was trying to establish its credit. Hamilton feared that all was lost if the agricultural classes remained dominant in the new government. Instead of a landed aristocracy or an agrarian democracy in which he had little faith, he wished to see a powerful industrial order such as was coming to the fore in England. He built his financial program around the banking and business interests of the North Atlantic States.33 Their support would be of little avail unless there were some assurance that the supply of industrial labor would increase, and that wages would remain relatively low. Cheap land would lure labor from the East and cause wages to rise. Concentration of labor on farm lands would, he feared, produce an agricultural surplus.

On the other hand, Hamilton had no desire to bring more money into the treasury than was necessary to establish credit, because a surplus would remove one very plausible reason for enacting a protective tariff. He did not oppose immigration, but he insisted that the flow of incoming labor should be regulated so that the economic order could easily absorb it. In short, then, it would seem that Hamilton desired not only to use the public domain as an important source of revenue for the United States treasury, but also to dispose of it in such a way as to guarantee a stable economic and social order.34 It is not surprising, therefore, to find Hamilton in 1790 proposing that public lands be sold at 30 cents an acre and in lots not larger than 100 acres each.35 He apparently felt that low-priced land set off in tracts too small to be conducive to speculation would bring more money into the treasury than large tracts sold to speculators who could not meet the terms of their contracts. This does not mean that he was opposed to offering the land in large tracts, that is to say, townships of even uncertain size. In truth he hoped the day would soon appear when men of money would buy large tracts at prices far above the 30 cent minimum.

It was the condition of the United States treasury which finally led to the passage of new land legislation. Two committees of the House, the Committee on Ways and Means and a Land Committee, were working toward the same end -- the reduction of the public debt. The bill when first reported embodied little change from the provisions of the Ordinance of 1785. The Land Committee realized the great difficulty of formulating a new policy, for upon presentation of the bill the chairman invited thorough discussion of the whole public land question. A storm of debate broke loose. Before the House was through with the matter practically every principle of the land system had been discussed.

This bill was not a liberal measure. It provided for selling land in lots three miles square, which at $2 an acre would cost $3,840. Scarcely had the House begun its consideration when various members demanded sale of land in smaller tracts and on more lenient terms. Representative Robert Rutherford, who had lived on the frontier of Virginia for many years, hoped that Congress would destroy that hydra -- speculation -- which had done the country great harm. Let the government, said he, dispose of this land to original settlers; a hundred and fifty thousand families were waiting to become occupants. Moreover, he added, the "monsters" in Europe were ready to join the "monsters" here, to swallow up this country. John Nicholas of Virginia observed that if the bill were to be changed and provision made for sale in small lots there would be no encouragement for men of property to come forward, for the best lands would be bought by farmers and none left. William Findley of Pennsylvania was opposed to any policy which would engross land into the hands of the few. "Land," he declared, "is the most valuable of all property and ought to be brought within the reach of the people."36

At this juncture Albert Gallatin, representing the frontier region of western Pennsylvania, arose and presented an amendment providing that part of the land be surveyed and sold in small tracts. He claimed that the public debt could thus be extinguished in ten years, and he was in favor of the plan that would bring in the most money. A certain proportion of farmers, he observed, men of small property, who were able to pay for land and remove to the West, would purchase; at least, he wished to give them the opportunity. The farmer, according to Gallatin, would not buy land to sell, and he reminded his hearers that poor persons must purchase on long credit and pay out of profits from the land. So far as he was able to comprehend, there were only two sets of interests opposed to the opening up of the public domain: those of the self-centered speculators, and those of the vested interests of Easterners who feared too great an emigration from the Atlantic States. Gallatin claimed that before the Revolution the policy of favoring the actual settler prevailed from one end of die country to the other, and that to this principle a great deal of happiness and prosperity was due. "If the cause of the happiness of this country was examined into," he conjectured, "it would be found to arise as much from the great plenty of land in proportion to the inhabitants... as from the wisdom of their political institutions."37

William Cooper of New York, one of the leading speculators in lands of his state, claimed that in the history of land sales in Pennsylvania and New York, where land was sold in small lots, there were not twenty instances of farmers buying it. Gallatin retorted that the gentleman was totally mistaken. With respect to Pennsylvania, he would maintain that not more than one thousand men had purchased large tracts, the other seventy thousand were possessors of small tracts. Supporting Gallatin in his stand were Edward Livingston and James Madison, later to become prominent in the Jefferson administration.38

Gallatin's amendment was adopted, and before the House was through the bill had acquired a markedly democratic character. Unfortunately, the Senate refused to accept Gallatin's changes and as finally signed the measure was far more favorable to speculators than to actual settlers.39

This Act of 1796 retained the basic institutions of rectangular survey and auction. The minimum price, however, was raised to $2 per acre as compared with $1 under the Ordinance of 1785. Approximately half the lands were to be disposed of in tracts containing 5,760 acres, the rest in tracts of 640 acres. This was quite different from the 160-acre tracts proposed by Gallatin. An unattractive one-year credit provided little inducement to settlers to take up land. The best feature of the act was the provision establishing local land offices at Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. Indeed, it is little wonder that dissatisfaction with the national land system began to grow immediately after 1796.

Since only the exterior lines of the townships in the first seven ranges of Ohio had been run under the Ordinance of 1785, it was necessary to divide the townships before any 640-acre tracts could be sold. There were delays in the appointment of a surveyor-general and his staff; Congress was slow to appropriate the necessary money; every tract had to be fully described as to nature of soil, rivers, etc., a process which took more time than had been expected. By 1800, only fifty thousand acres of land had been sold under this act, and by that time politicians were beginning to realize that a more attractive and effective system was essential.

Conditions in the western country were indeed in a muddle. Squatters were appearing in choice localities. Numerous petitions were pouring into the Treasury Department and into Congress asking for a more liberal land policy. One of these, dated 1798, from a group of squatters on the Scioto River asked that a tract of land thirty miles square be set off, one-half to be surveyed into tracts containing 160 acres and the other half, 640 acres, and begged leave "to suggest whether it would not tend to the more speedy settlement of the lands and bringing the Value Thereof sooner into the publick Treasury was the price lowered or the present mode of sale altered." The newly-appointed Surveyor-General of the United States, Rufus Putnam, anxiously called the attention of the Secretary of the Treasury to the fact that the population along the Scioto was growing daily and that these people meant "to hold the Lands by Settling or without purchasing provided their members should increase so far as to give them a prospect of Succeeding in a measure of that kind."40 Governor St. Clair expressed the belief that these inhabitants on the Scioto, and others on the Great Miami -- altogether about two thousand in number -- would buy their lands, but that few would be prepared to pay for more than 160 acres at $2 an acre. Again he reminded the government that "in Pennsylvania, under its proprietary Government, the people were indulged in taking up lands in quantities not exceeding three hundred acres, on credit, at a moderate price." And he concluded with the terse warning that "very considerable difficulty may attend" any attempt to remove these settlers.41

Events in the nation at large were now moving toward a climax. Already the democratic forces under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson were exerting noticeable influence on national legislation. Such tendencies in the national political firmament naturally found reflections in the newer agricultural regions of the country. In 1799 Congress advanced the Old Northwest to its second stage of territorial government under the provisions of the Ordinance of 1787. The territory elected William Henry Harrison to the position of delegate to Congress. Harrison at once established his reputation by conspicuously launching a plan to reform the land system.42 As chairman of the land committee of the House of Representatives, he successfully defended the bill against the opposition of many capable minds. He demonstrated the dangerous consequences of the old system which resulted in preventing sales to actual settlers and encouraged the engrossment of extensive tracts of land by nonresident proprietors. Aiding Harrison in the framing of the bill was the discriminating genius of Albert Gallatin, who had crusaded in 1796 for a liberal land measure and who was soon to become Secretary of the Treasury under Jefferson.43 In spite of the fact that the bill became an act before Jefferson was elected President, the measure was a product of those democratic forces that were bringing into being a new era.

This act of May 10, 1800, is one of the most important measures in the history of the public domain.44 It provided for a liberal credit system, a reduction in the minimum amount of land to be offered for sale, and establishment of administrative machinery. Local land offices were to be opened in Cincinnati, Chillicothe, Hamilton, and Steubenville, each with a register and receiver paid from fees. The minimum amount of land that could be purchased was reduced to 320 acres; the minimum price was kept at $2 per acre. While a discount of 8 per cent was allowed for cash payment, more important was the fact that liberal credit was tendered to the settler. One-fourth part of the purchase price was due in forty days, a second fourth in two years, a third in three years, and the remaining fourth in four years. W. C. Claiborne of Tennessee attempted to have the principle of preemption included in the act, but eastern interests voted this down.45